Eradicating the One Percent

The swamps and subdivisions of southern Florida are overrun with invasive reptiles, including Burmese pythons and Nile monitor lizards. The only way to eliminate every last one of them is to follow the DNA trail they leave behind.

Article body copy

Tim and Patty O’Hara were looking forward to living out their golden years in the tropical city of Cape Coral on southern Florida’s Gulf Coast. Cape Coral is known as the Waterfront Wonderland because it has over 600 kilometers of canals—more than any other city in the world—and the city boasts that it has an average of 355 days of sunshine per year. When the community was carved out of the mosquito-infested mangroves and salt marshes back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, developers brought in celebrities like Bob Hope and Anita Bryant to give it a touch of wholesome glamour.

In September 2013, the O’Haras moved from Gig Harbor, Washington, to a neighborhood off Skyline Boulevard. Their retirement home was painted the color of rosé wine and had a neatly trimmed front lawn and a backyard pool. And like many of the city’s 165,831 residents, the O’Haras had a freshwater canal running behind their house, with the occasional boat floating past.

“We just wanted to goof off all the time,” Tim says. “To swim and play golf.” Tim’s sister and brother-in-law were avid birdwatchers, and the first time they visited they were blown away by all the nature around them, not only birds, but manatees, otters, and Florida redbelly turtles. A colony of burrowing owls—a protected species in Florida—had taken up residence on the empty lot next door. “They think that’s cool,” Tim says. He did, too.

It wasn’t long before the O’Haras started hearing about another animal in the area: the Nile monitor lizard. “Everybody talks about them,” Tim says. He’d seen a strange lizard around but didn’t know what it was.

About a year ago, their landscaper pointed to the corner of their yard. “There’s one right there,” he said. It was huge. It could easily have swallowed a family of owls and still have had room for a poodle.

How many cute burrowing owls can a Nile monitor dine on? A lot. The birds are only slightly larger than American robins. Photo by Gerald & Buff Corsi/Visuals Unlimited/Corbis

Native to Africa, the wily, semiaquatic lizards can reach lengths of up to two meters and weigh about seven kilograms. Smaller than a crocodile and larger than an iguana, monitors are—like foxes in the mammalian world—in the middle of the food chain in the reptilian world. They have a mouth full of pointed teeth and recurved claws that can put a line of stitches in a person, but their most fearsome weapon is their tail, which they use like a whip. Tim immediately picked up the phone. “I called the city, and they sent a guy out to trap it,” he says.

Over the next year, the O’Haras would keep that number close at hand and come to play a small but integral role in a scientific study that seeks a better way to track invasive species in coastal areas. Just as criminal detectives obtain DNA samples from straws or cigarette butts discarded by suspects, wildlife biologists have learned how to detect and gather distinctive genetic signatures that animals leave behind in the environment. Fragments of DNA present in dead skin cells, hair, or feces can survive days, or even weeks, after an animal has passed through a body of water. This environmental DNA, or eDNA, is a groundbreaking new tool that throws a spotlight on the spread of exotic species.

The woman leading this revolution in Florida’s swamps and suburbs is Antoinette “Toni” Piaggio, a molecular ecologist with the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Wildlife Research Center in Fort Collins, Colorado. Piaggio has developed eDNA tests for introduced Burmese pythons and feral pigs and soon hopes to have one for the Nile monitor. “We certainly can’t do anything about them until we know exactly where they are,” she says. “When you are controlling invasive species, it’s those last few that are the hardest to find.”

But to start tracking the lizards, she needed a fresh one. What was unwelcome news for the O’Haras would be good news for Piaggio—and the war against invasives in Florida.

Melting Pot

With temperatures that rarely dip below freezing, southern Florida is like the glassed-in reptile hothouse at the local zoo—except there’s no glass to confine the creatures. Take a walk around the O’Haras’ neighborhood and you’ll find a menagerie straight out of the pages of National Geographic. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, more than 500 species of non-native reptiles, amphibians, birds, mammals, and fish have been spotted in the state. About 100 of those species have established breeding populations, and there are now more species of non-native lizards breeding in Florida than native ones.

Most of the non-native reptile species ended up here because of the global pet trade. There are the green iguanas and spiny tail iguanas, which are native to Mexico and Central America, and the over-a-meter-long black-and-white Tegu lizards from South America. In trees and shrubs, you might spot a veiled chameleon, which hails from Saudi Arabia and has a prehensile tail and an enormous casque on its head.

The most famous cold-blooded invader in south Florida is the Burmese python—a tough species to detect. Burmese pythons could number over 150,000 and are so voracious they’ve taken to gobbling up just about everything they can get their suffocating coils around inside and outside of Everglades National Park.

Burmese pythons are probably the most famously unwelcome invasive species in Florida. Photo by Joe Skipper/Reuters/Corbis

Rumor has it that Nile monitors arrived in Florida when a pet dealer intentionally released them in the 1990s to create a breeding population. Actually, it looks like several people may have had the same idea. “It’s pretty obvious that there are three clusters,” says Harry Phillips, an environmental biologist with the City of Cape Coral. One population is right in Cape Coral, and the others are on the Atlantic coast in Palm Beach and at the Homestead Air Reserve Base near the Everglades. Early on, Phillips says, Cape Coral officials thought they might eradicate the city’s Nile monitors, but it took them 10 years to give up that dream.

Now, the city handles the monitors on a case-by-case basis. People spot a lizard. They make a call. The city puts out a trap and checks it every two weeks. “It’s a kind of a bait-and-wait situation,” says Phillips. “We can’t be there all the time.” Out of a population of about 700 to 1000 Nile monitors, his team catches about 50 to 70 a year, which is about the same number of eggs that one large female can lay in a year.

The trapping only keeps the population in check. Nile monitors can find safe refuge in vacant lots and foreclosed properties, especially in places where people are less likely to spot, and report, the lizards. “If we were to put out a full-on assault on the Nile monitors and take it out of the control phase and into the eradication phase, it would boil down to having a task force that goes out on a daily or weekly basis and singles out those areas to get the last few individuals,” says Phillips.

They might find some of those individuals by looking for tail drags, claw imprints, or burrows. But it’s incredibly difficult to find the last few elusive individuals amid all those canals, empty lots, and densely vegetated parkland. For the effort to be successful, it would come down to eliminating that final one percent. Which is why Phillips looks forward to the day when testing for their presence could be as simple as collecting a few liters of water and bringing it back to the lab.

In late March 2015, the O’Haras called the city to report another monitor slinking in the vicinity of the burrowing owls. Phillips had his team deploy a large trap—actually two large metal mesh traps stitched together. Then, they baited it with raw chicken backs.

Days later and … snap! The trap clicked shut.

They had themselves a big one: nearly two meters from the tip of its nose to the tip of its tail. Afterward, John Humphrey, a wildlife biologist with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), loaded the lizard into a plastic carrier labeled “Danger Reptiles” in big red letters and drove it to the USDA lab in Gainesville.

Look who moved into the neighborhood: introduced Nile monitors in Florida. Photo by Melissa Farlow/National Geographic/Getty Images

There, he put on a pair of Kevlar gloves and plunged the lizard into a water-filled trash can. After 20 minutes, he withdrew three liters of water from the can, froze it, and shipped two liters to Piaggio’s lab, where the lizard’s DNA was about to betray its entire species.

Gene Sleuthing

At the National Wildlife Research Center, Toni Piaggio has just wrapped up a business meeting. With her tailored suit and high heels click clacking along the hallway, she looks more like a CEO than an ecologist, but then she casually mentions that she has a bunch of feral pigs in the back, lounging around in muddy wallows filled with “pee and poop.”

Piaggio works with the USDA’s Wildlife Services, which is trying to control or eliminate feral swine in 39 states, including Florida. Her graduate student developed a test to detect the pigs through eDNA and is studying how long it takes for the DNA to degrade. In practice, field technicians might use the test to sample puddles and ponds to find out if pigs have recently been in a certain area and to ensure places where pigs have been eradicated remain pig free. In the coming year, eDNA monitoring will complement the agency’s surveillance work, which relies on camera traps, aerial surveys, and human trackers. One effort in Florida will focus on St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge, an undeveloped barrier island on the Florida panhandle where feral pigs prey on the eggs of nesting birds and sea turtles.

For most of her career, Piaggio has specialized in what researchers call noninvasive DNA—jargon for DNA that doesn’t come directly from blood or tissue. Instead, she obtains samples from piles of dung or hair stuck on barbed-wire fences or purposely placed hair traps. Noninvasive DNA samples are tough to analyze because they are easily contaminated with DNA from other life forms; eDNA presents even more of a challenge because it is dispersed in low concentrations in water, soil, or air. But, when eDNA is successfully collected, the payoff is great because it allows scientists to identify the presence of a species even when it has left no visible traces behind. In other words, it gets researchers that much closer to finding every last individual.

Paleoecologists conducted the first eDNA studies when they reconstructed life in ancient environments by taking samples from ice cores or sea-floor sediments. It has also been used to track the spread of wildlife diseases by monitoring viral DNA and to census hard-to-find native species, like the eastern hellbender salamander, the largest salamander in North America and a species of special concern. The eDNA technique got its first high-profile test in the invasive-species world when David Lodge at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana and his colleagues detected the genes of two species of Asian carps north of an electric barrier that was supposed to keep Lake Michigan carp free. Eight months later, a commercial fisherman pulled an adult bighead carp out of that same area, confirming the result with cold, fishy proof.

Piaggio started thinking about applying eDNA analysis to large terrestrial vertebrates. She mused over, for instance, how much DNA might remain if a deer lapped up water from a stream or if a bird took a bath in a puddle. But Florida’s Burmese pythons were already on the USDA’s radar, and Piaggio knew they spent a significant amount of time in water, so she decided to tackle the snake. After succeeding in isolating and amplifying DNA fragments from water that came in contact with pythons in the lab, she tested the technique in nature. Her team visited six field sites in southern Florida and confirmed the presence of python DNA in the five sites where pythons had previously been spotted.

Now, scientists use the method to better estimate the distribution of pythons in Florida. “You are looking for a little bitty piece of DNA in a waterway,” she says. “If we get a positive test, we know that a Burmese python has shed DNA in the past seven days. Can we tell you exactly where it is? No. Can we tell you how many snakes there are? No. The science still has a long way to go.” Part of pushing the science forward involves applying the techniques to new species, such as Nile monitors, and testing how well they work in the field.

Every day on her way to her office, Piaggio walks past a glass display case showing all the traps used by the USDA over the years to control wildlife, including a square-shaped beaver and otter trap and a frightening jaw trap for wolves—reminders that much of the work of the USDA’s Wildlife Services over the last century has been about eradicating native predators to protect crops and livestock. Today, all that expertise is being directed toward invasive species. “In my lifetime, I’ve seen so many changes to ecosystems and a lot of that is from humans,” Piaggio says. “Humans moving plants and animals around and bringing in new predators and pathogens that affect endemic species.”

Down the hall from the display case, Piaggio’s eDNA laboratory looks like a standard genetics laboratory with boxy gene sequencers and other equipment arranged on a black counter. But because eDNA exists in such low concentrations, she maintains two separate labs to avoid contamination. In the back of the room, one of Piaggio’s technicians opens a freezer cooled to -80 ˚C, where a half dozen Nalgene bottles are lined up like frost-covered soldiers.

The technician pulls out a bottle containing eDNA from Tim and Patty O’Hara’s Nile monitor and sets it on the black counter. The laboratory work on monitors began earlier this summer. First, Piaggio’s team is looking at a fast-evolving segment of the genome that lizard researchers said can be used as a genetic barcode to scan lizards the way a clerk might scan the items at a grocery store. Piaggio needs to confirm whether this gene sequence could distinguish Nile monitors from other lizard species in Florida. Secondly, she wants to see if the technique can separate the Nile monitor from other exotic pet monitors, such as the Savannah monitor, another African native that has been spotted in the wild but may not have established a reproductive population.

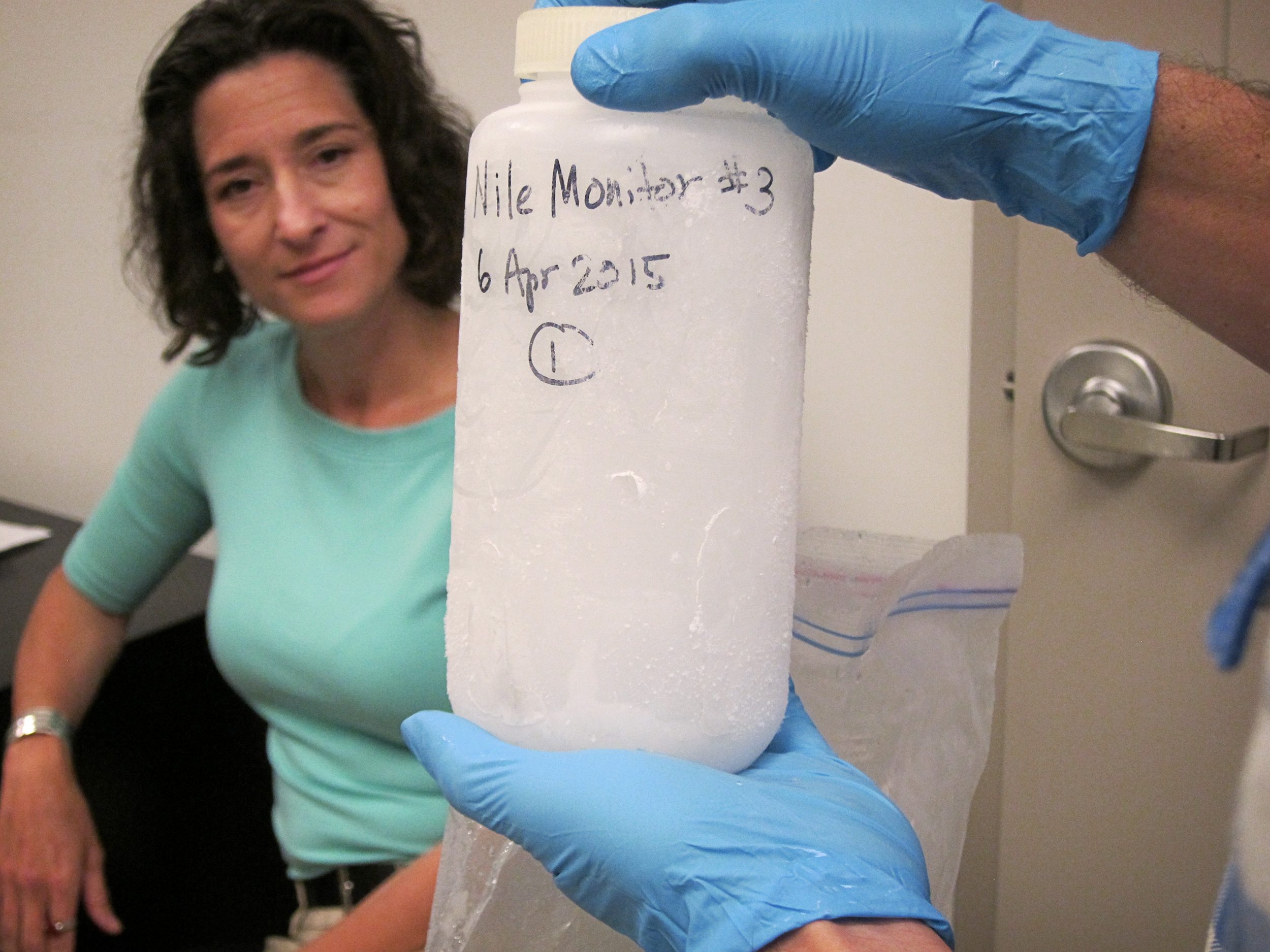

Researcher Toni Piaggio looks on as an assistant holds up a frozen bottle containing DNA from a Nile monitor. Photo by Brendan Borrell

Of course, no matter how well the method works on the creatures, it’s a lot tougher to keep tabs on people, such as the guy who released those monitor lizards in the first place. Under Florida law, reptile fans are no longer allowed to own Nile monitors, Burmese pythons, anacondas, or five other harmful species of snakes without a special permit. But no one is going house to house to make people comply with the law, and the laws aren’t as strict in neighboring states. In fact, Piaggio says she recently received the carcass of a Nile monitor that turned up in another southern state. Which state? She wouldn’t say. “It’s a state where they are not supposed to be.”

As Piaggio cranks away at the science, the O’Haras are doing their part to keep an eye on invasive species the old-fashioned way. Every time Tim walked his dog this past spring, he stopped to admire the brood of burrowing owl chicks—all six of them—playing in the bushes in front of his house. Before the little ones left the nest in early July, he took a couple photos for his brother-in-law and then went on vacation. By the time he came back, a Nile monitor was already scoping out the place.