The Guardian Angel of Swimming Children

Joe Fortes, Vancouver’s first official lifeguard, taught thousands of youngsters how to swim and saved more than 100 lives.

Article body copy

Postage stamps are lessons in history, politics, science, or geography packed onto a small piece of gummed paper. They’re also beautiful works of art. In Stamped we’re going coastal, with postal.

At precisely 10:40 a.m. on February 7, 1922, work stopped in every classroom in every public school in Vancouver, British Columbia. The day’s lessons were interrupted so that teachers could expound on the heroic deeds of Joe Fortes, who at that moment was being buried in one of the grandest public farewell ceremonies the city had ever held.

The children needed little reminder about Fortes, the longtime lifeguard and swimming instructor at English Bay, a sandy beach mere steps from the growing metropolis. Indeed, some of the older pupils even owed him their lives.

Named Seraphim at birth after the highest rank of angels, Fortes left his home island of Trinidad as a teenager to work as a deckhand aboard a brigantine carrying sugar. After living in Liverpool, England, for a few years, he signed on as a crewman aboard a merchant vessel bound for Vancouver Island. On the way there, the 58-meter boat struck a rock and barely limped into Vancouver, which at the time was a rough mill town cut out of the coastal rainforest along Burrard Inlet. With his ship undergoing repairs, Fortes worked odd jobs before becoming a bootblack at a waterfront hotel in Vancouver. He enjoyed life in the fledgling port and never returned to sea.

On June 13, 1886, a fire swept through Vancouver, destroying everything in its path. Fortes rescued a woman and her son from his hotel—a brave act and a first taste of the heroism that would become his life’s theme. The townspeople rebuilt and Fortes became a bartender of renown, skilled at mixing drinks and strong enough to dissuade even the most belligerent of drunks from brawling. He became known as Joe, likely after the Stephen Foster song “Old Black Joe,” and went for regular swims at what was then a little-used beach. As the city grew, many others joined him in the water. He served as a volunteer lifeguard and swimming instructor until the city finally hired him for those duties. The police even made him a special constable for the beach. His bartending days were over.

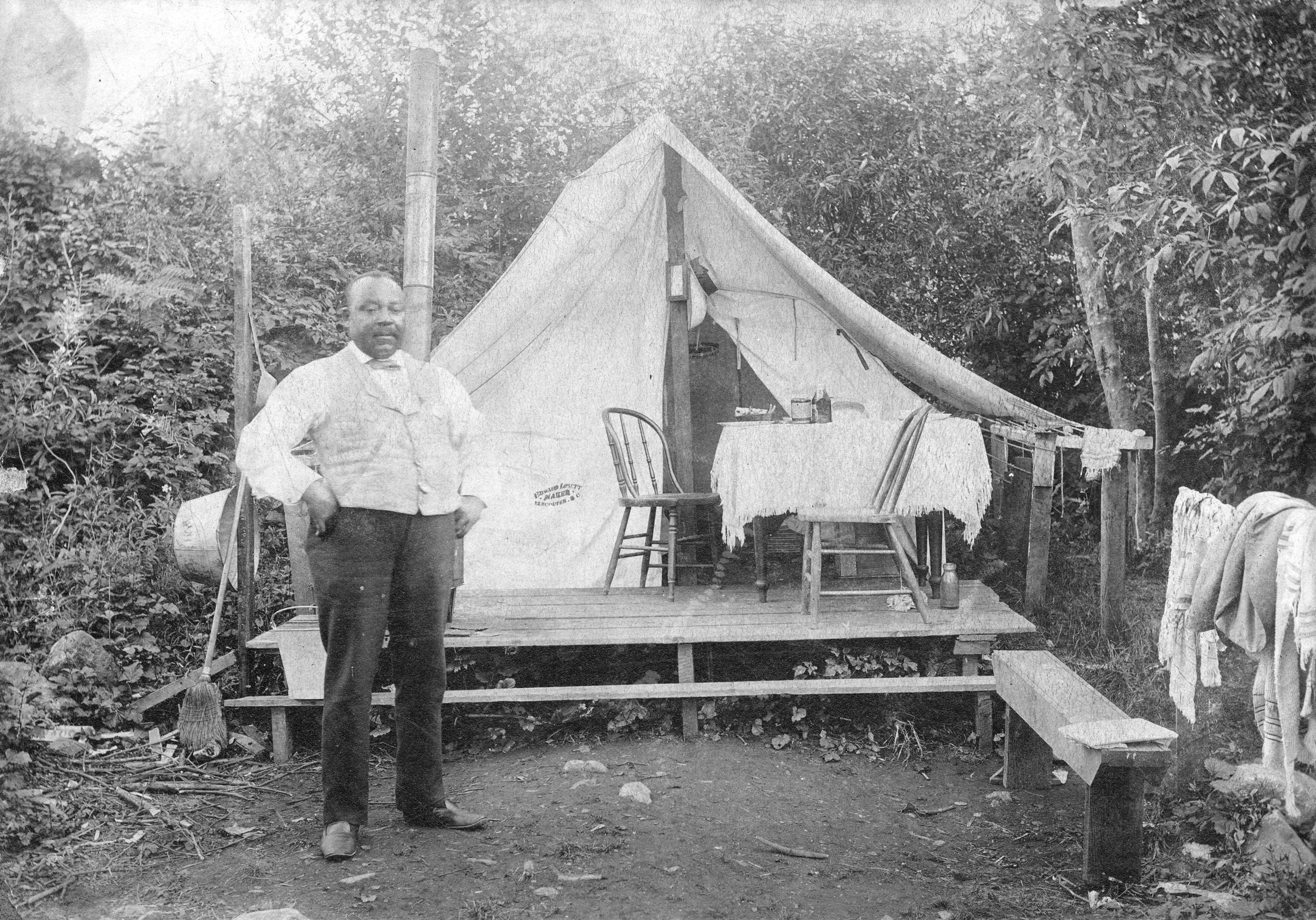

In summers, he lived in a tent on the beach, spending four hours each morning and another four hours each afternoon in the water, wearing a woolen singlet stretched over an ample belly, surrounded by children. “Kick yo’ feet, chile!” he’d shout. He so loved salt water, it was said that he drank a daily glass of brine as a tonic.

At home by the ocean, Joe Fortes lived in a tent on the beach during the summer. Photo courtesy of City of Vancouver Archives

As well as teaching thousands of children to swim, Fortes is credited with saving more than 100 people from drowning. One of his first rescuees was John Hugo Ross, the young son of a member of Parliament, who became a prominent businessman before drowning in the sinking of the Titanic.

In an era when anti-black violence in the United States was common, his time in the city was not without racial animus. At least one anonymous correspondent to a city newspaper complained about a black man bathing alongside white women and children.

Today, the Fortes name remains revered. In 1927, the city unveiled a drinking fountain at a park near English Bay with an inscription reading, “Little children loved him.” A nearby library branch carries his name, as does a popular seafood restaurant. In February 2013, to mark Black History Month, Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp depicting Fortes in his trademark woolen swimsuit in front of a panorama of his beloved beach.