We Have Unrealistic Beauty Standards for Coral, Too

Virtual reality experiments show people value pretty reefs over healthy ones.

Article body copy

Vibrant images of coral reefs are popular features in glossy travel magazines. This spiraling kaleidoscope of neon corals leads many to believe that “pretty” must also mean “healthy.”

But according to Julie Vercelloni, a marine scientist at the University of Queensland in Australia, something more sinister is often at play when corals turn a fluorescent shade.

“It [can be] a sign of death. Bright coloring is common in the early stages of a bleaching event,” she says. “It’s beautiful, but not sustainable.”

Like the extreme beauty standards propagated by the fashion industry, new research suggests that our overexposure to only the most visually striking coral reefs is shaping unrealistic expectations about what a coral reef should look like. The use of artificial lighting, pumped up colors, and heavy editing in documentaries and photography pushes these boundaries even further. This may affect which reefs people want to protect.

David Suggett, a marine biologist at the University of Technology Sydney, says the finding opens the discussion about how people may feel about coral reefs as they respond to climate change and environmental stress.

“Reefs will likely look very different as hardier coral species begin to recover, which are sometimes not as colorful or structurally diverse,” says Suggett. “We need to communicate what is truly healthy versus what looks good.”

The research echoes another recent demonstration of beauty bias. In 2016, scientists showed that even conservation scientists favor attractive, charismatic vertebrates over invertebrates that are critical to ecosystem health.

Still, aesthetic considerations matter, even if they’re less quantifiable than health indicators such as biodiversity and water quality, Vercelloni says. “If people think that the Great Barrier Reef is no longer beautiful, then they may think that there is no point trying to conserve it.”

Indeed, “exceptional natural beauty” and “aesthetic importance” are both listed as selection criteria for UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as the Great Barrier Reef.

Few studies, however, have attempted to pin down what exactly people find beautiful about the Great Barrier Reef. But taking a survey group to the reef was impractical, so Vercelloni and her team came up with the next best thing—virtual reality.

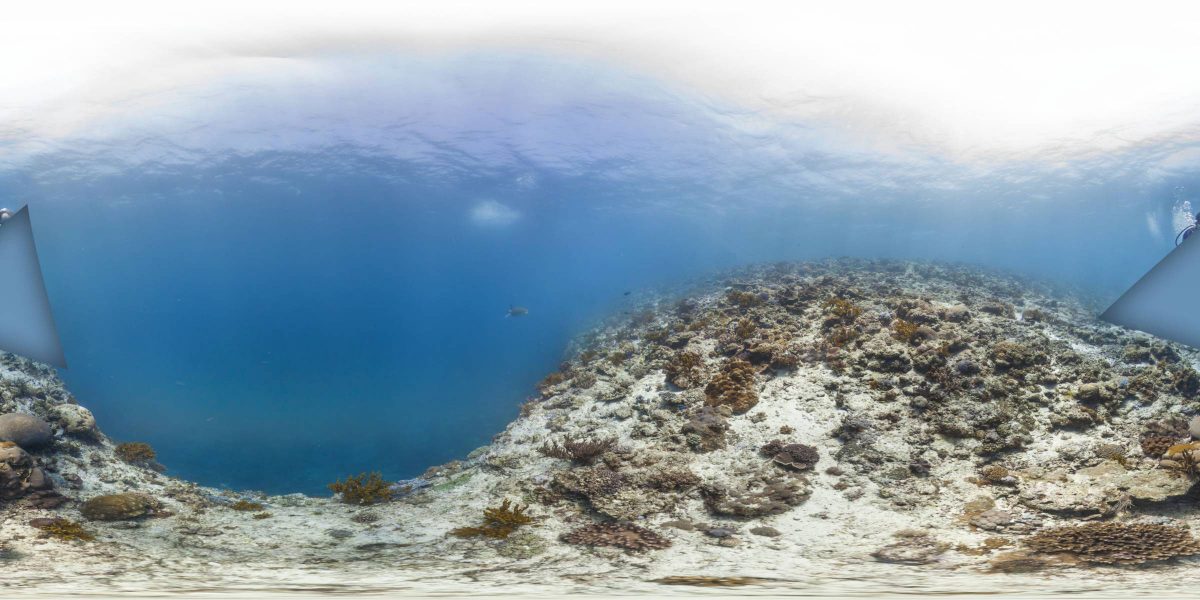

The researchers immersed groups of marine scientists, experienced divers, and regular citizens in 360-degree scenes showing both healthy and degraded areas of the Great Barrier Reef. Each participant was asked to assess how pleasing they found the images based on eight different attributes, such as water visibility, color diversity, reef damage, and the presence of different fish.

Study participants virtually explored a range of coral reefs, assessing them for their beauty. But what they found most appealing didn’t always reflect the health of the reef. Photos courtesy of Julie Vercelloni

Some of the ranking criteria represented a win-win situation. Reefs showing a diverse array of corals and fish, for example, are a sign of both beauty and health. All of the survey participants rated this attribute as aesthetically pleasing, though one group, the marine scientists, may have been biased toward this feature as they knew it represented a healthy reef.

The survey also showed that all three groups found colorful reefs the most appealing, even though a variety of hues don’t always point to good health. In stressed coral reefs, other colorful animals such as soft corals and sponges begin thriving. But a burst of fluorescent color may indicate that a reef is on the brink of bleaching.

The citizen group turned out to be the harshest critics of what they perceived as ugly reefs, likely because they are used to only seeing heavily photoshopped “perfect” reefs, Vercelloni says.

Citizen participants were also overzealous in identifying coral bleaching, seeing it in more than a quarter of the images, even though the images showed no bleaching. The images were taken prior to the massive coral bleaching event in 2016, which wiped out more than two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef. But there was wide coverage of bleaching in the media at the time of the survey, and these alarming reports may have led the citizen group to expect images of damaged coral. As a result, they saw flaws where there were none.

Understanding the features of a coral reef that people value can help focus conservation efforts to help maintain the reef-reliant economy, but only within reason. Vercelloni says promoting sustainable, functional beauty in coral reefs needs to be a higher priority when monitoring their ecology.

“It’s all about educating people to see the beauty in healthy reefs that can be sustained over time,” she says.