Evicted by Climate Change

Government regulations forced the Yup’ik to give up their semi-nomadic existence. Now, as the land around them vanishes, they’re puzzling through the problem of moving.

Article body copy

On a Sunday morning in late September, Tom John, a wiry fisherman with a deep, placid gaze, ushers me onto his boat, moored on a riverbank in Newtok village, in southwest Alaska. His wife, Bernice, a sturdy-shouldered woman with a voice as bright as a sparrow’s, and their nine-year-old grandson clamber in after me. Our footsteps clang against the aluminum hull. Bernice gestures for me to take shelter from the damp wind in a makeshift cabin built out of wood and a tarp. I nestle in beside coats, buckets, a mug, a cracker box, a camp lantern, an empty coffee jar. “We sleep in the boat when we travel out to the wilderness,” Tom explains. Virtually no roads cross this vast region known as the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta—or the “Y-K Delta” in Alaskan shorthand—an area roughly the size of the Mississippi River floodplain. People get around by boat—winding through the creeks and rivers that stripe the spongy tundra—by ATV, or by snowmobile. A handful of airlines operate flights to the Y-K Delta villages on propeller planes about as hefty as oversized mayflies; I arrived on one yesterday, after waiting two days for dense fog to lift at a rural airport.

Today we will float just a few kilometers upstream to check Tom’s fish traps. He shoves a long pole into the mud and nudges the boat into the gray-blue water. Bernice chirps instructions at her grandson in Yup’ik, the native, and still the first, language spoken in this region. In slow, clipped English, Tom says, “When we get to the old village site, I’ll show you where these people came from.” He yanks the starter rope until the motor sputters and then roars like a jackhammer.

By “these people,” Tom means the Yup’ik founders of Newtok. The Yup’ik represent one of Alaska’s 11 distinct native cultural groups and have lived along the Bering Sea for perhaps 2,000 years. Until a few decades ago, they maintained a nimble, semi-nomadic lifestyle, migrating between seasonal camps. Beginning each April, they were on the move, camping at the coast to hunt seals and then journeying up the rivers in search of fish. Around freeze-up, they settled back into winter homes made of sod and driftwood.

The John family, like most families in Newtok, still relies on food hunted on or gathered from the tundra. Photo by Madeline Ostrander

Yup’ik people started to camp at Newtok in the late 1940s, after having problems with flooding at their previous winter village. They picked the site with a different priority in mind than usual: it was the farthest point upriver that a barge could reach. The federal government had mandated that all native children must receive formal education, even if it meant packing them off to boarding schools hundreds of kilometers away from family. With access to supplies from commercial ships, the community could have a school and keep its children close. By the early 1960s, Newtok’s first school—built by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)—was up and running. The village grew around it; today, it’s a collection of ramshackle cottages and modular office buildings, knit together by broken and slippery wooden boardwalks, and permanent infrastructure no longer suitable for nomadic life, including a power plant and a water treatment facility. By the 1970s, the people had become stationary, too.

Even in the early days at Newtok, its residents could see that the tundra was warming and thawing, and that the river was eating the land around them. In the past few years, they have become famous, heralded by the international press as “America’s first climate refugees” (along with residents of two other Alaskan villages and a tiny Louisianan island community). Newtok is one of the first places in the United States that could be erased by the impacts of climate change. The US Army Corps of Engineers has estimated that erosion will ravage much of the village within the next decade.

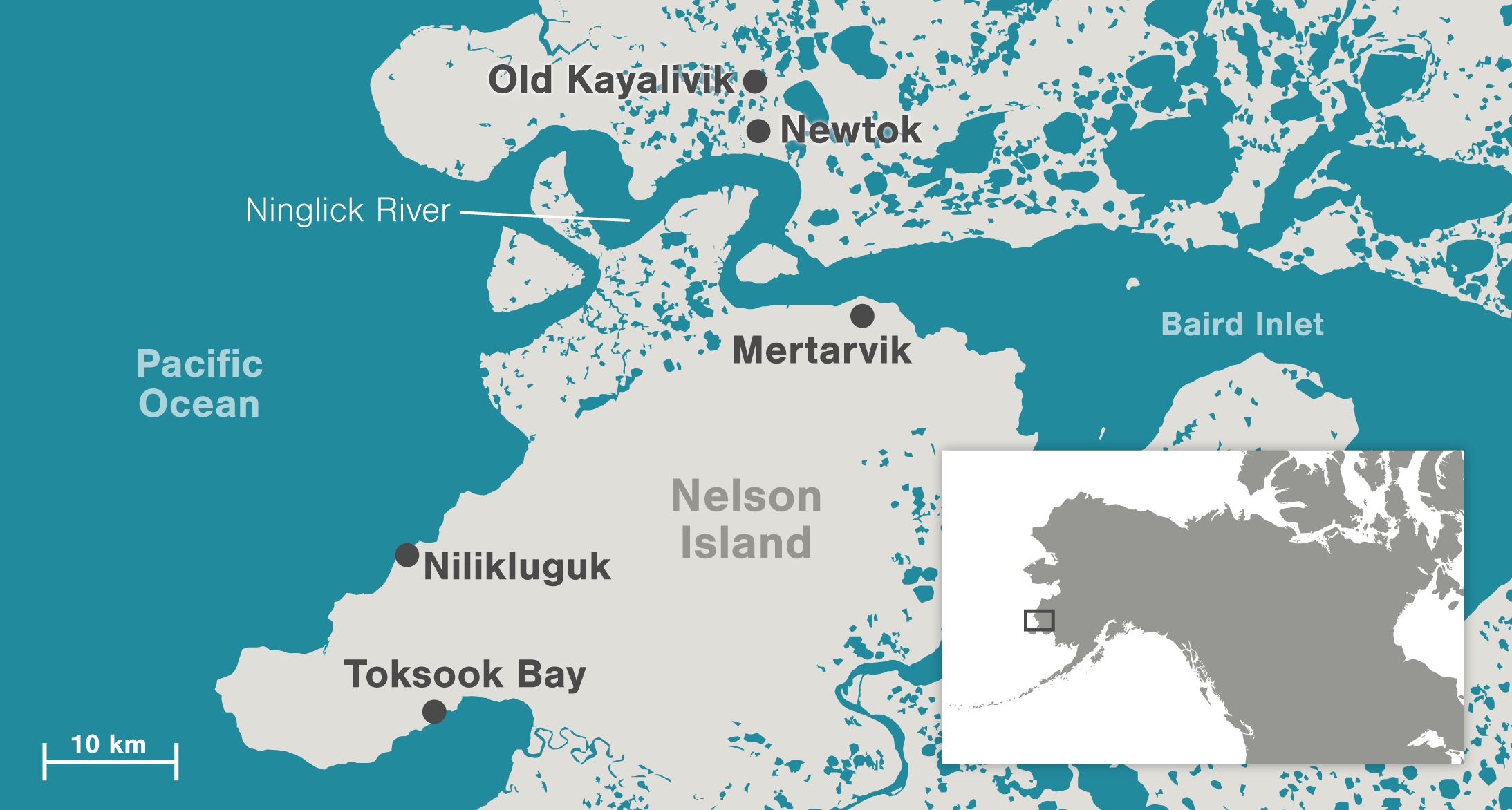

The Ninglick River has been steadily consuming the bank that Newtok sits along at an average rate of 21 meters per year. The riverbank is now 55.5 meters from the nearest home. Illustration by Mark Garrison (based on the Arctic Slope Consulting Group’s Newtok Erosion Shoreline Map)

For 20 years, the residents of Newtok have struggled to find a way to move the entire community to safer ground. Newtok perches precariously in a space where two cultures collide. The old tradition of moving with land and seasons has faltered under the weight of permanent architecture and infrastructure forced upon the Yup’ik by modern society. To be permanent and stationary requires a community to stand its ground against the will of nature. But that’s always been a difficult prospect in a place ruled by tumultuous cycles of storms and ice. Now a warming climate is making it impossible.

For the people of Newtok, relocating means turning back to traditions while still bowing to the demands of modern life. It requires raising millions of dollars; navigating complicated bureaucratic processes; and negotiating with everyone from the regional school district to the Alaska State Legislature and the US Congress. And even after all of these hurdles are passed, the bad-tempered tundra weather can foil the best-laid plans, stranding boats and grounding planes, flooding, howling, and raging.

That makes the move a grand experiment and the people here less like refugees and more like pioneers trying to chart a new path across the thawing landscape. To be a nomad is to move when the earth changes. Few people know how to do this skillfully. But the Yup’ik can remember.

Tom steers the boat along the Kealivik (or Kayalivik) River, a tributary of a larger, more powerful river called the Ninglick. Tawny grasses and shrubby, yellow-leaved willows stretch from the banks to the horizon as far as the eye can see. In the distance behind us, Nelson Island appears in a shroud of low clouds, its rocky ridgeline faint and blue in the haze.

The water is glassy, and the river is bloated from swallowing both rain and tundra soil. Bernice points at a muddy bank ripped open by the river. “See where it’s eroded?” she shouts above the din. “It only stops when we’re frozen.”

Water, ice, and soil form this landscape—part swamp and part permafrost. The community started reporting erosion problems to officials in the 1970s. In the early 1980s, the Alaska legislature gave Newtok money to hire engineering consultants to study the problem. The engineers noted that relatively warm temperatures were melting the bits of ice that bind the soil together, making it possible for the Ninglick River to tear apart the ground. Climate change will likely stir more intense waves and storm surges here. As the unfrozen season lengthens, the land is weaker, the river stronger and more destructive. Between 1954 and 2003, the Ninglick ate about nine American football fields worth of the land separating the village from the water.

When it became clear that the swollen river’s appetite couldn’t be sated, Newtok leaders began planning in 1994 to relocate. A site about 15 kilometers south of Newtok called Mertarvik, meaning “place to get water” in Yup’ik, on the volcanic bluffs of Nelson Island, looked like one of the best options. More than 35 times the size of Manhattan, Nelson Island is home to about 1,200 people in four communities with long-standing cultural and familial ties to Newtok. The people of Newtok camped all summer on Nelson Island at a place called Nilikluguk, until a landslide buried it in the 1960s. The villagers still hunt on the island and stop at Mertarvik to gather water from a spring. But moving there permanently is more complicated. Y-K villages exist as islands of private land within publicly owned territory—the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge, designated in 1980, encompasses most of the delta. Any exchange of land from the refuge requires federal government approval. In 2003, after years of negotiations, Congress finally authorized the transfer of Mertarvik land to the people of Newtok.

The people of Newtok have begun a slow, incremental migration to Mertarvik on Nelson Island. Photo by Andrew Burton/Getty Images

Even after they got the land, the Newtok residents still needed to raise vast sums of money and run the gauntlet of perplexing legal requirements. They banged on the doors of government bureaucrats, pleading for help. But government agencies lacked authority over or experience with moving an entire community threatened by climate change. Still, by 2006, they had assembled a committee of public servants and nonprofit organizations called the Newtok Planning Group. That same year, the federal government gave the villagers enough money to build just three of the 80 houses they would need at the new village. A year passed before the community found a barge company willing to drop housing materials in the wilderness—at a site with no landing or other commercial infrastructure—and another year to construct the homes, though they have yet to be moved into final position and remain unoccupied.

The US Department of Defense led summer training exercises at Mertarvik from 2009 to 2013, both to set the new village’s foundations and to teach troops how to create a base in the wilderness. Military personnel erected storage buildings, carved out a quarry, built a barge landing, and laid down an access road.

In 2012, the community built three additional government-funded homes at Mertarvik. A handful of community members volunteered to move there first. They live with no running water or electricity, sometimes returning seasonally to Newtok so they are not isolated during the harshest weather. The villagers call them “the pioneers.” This phase of the community’s transition to Mertarvik is the upagluteng, a word that harks back to the practice of moving with the seasons. The community requires more than US $60-million for the extra houses and associated infrastructure needed to relocate the rest of its 400 or so members—and that figure doesn’t include other essentials, such as a school or an airport.

In the boat, we head north, away from Nelson Island and toward the place the people of Newtok came from—the flood-prone winter village they left behind only one or two generations ago. It bears the same name as the river: Old Kayalivik. We arrive in about 20 minutes, and Tom slows the motor, which cuts out and begins to beep. “The grassy area,” he says, gesturing for me to look beyond the bank to our left.

If all goes according to plan, the community of Newtok will resettle at the site known as Mertarvik, roughly 16 kilometers to the southeast, within the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge. Illustration by Mark Garrison

Eager to reach his fish traps, Tom doesn’t let us go ashore. But across the flatlands, I can see a few tilted wooden crosses and fences marking old graves—the influence of missionaries. The land rolls up around them into a set of knolls. These are the remnants of sod houses, since reclaimed by grass. They are so crumbled and overgrown that they are barely visible from here.

The Yup’ik built winter villages centered around a sod structure called a qasgiq. Bernice explains that Old Kayalivik would have had such a building—a round, multifunctional space that served as a town hall, a ceremonial hall, a residence for men, and a place for learning. The qasgiq was a space for holistic activities that maintained the community’s physical and spiritual well-being.

Bernice tells me her parents and grandparents lived in this village. “I never got to experience it myself,” she adds. Tom jerks the starter rope, and the motor rattles into action again. “If we were living [their] lifestyle,” Bernice shouts, “we wouldn’t be living in this situation.”

Today, more than 20,000 people, most of them Yup’ik, inhabit the Y-K region in several dozen villages that often look like a cross between a military outpost and a fishing camp. Families live crowded in spartan, boxy, wood-framed houses—usually government issued—some without running water or flush toilets. The early villages were often smaller, more scattered, and more numerous than today’s. Their culture and economy revolved around hunting and fishing.

The Yup’ik still depend on food that they can hunt, fish, and gather from the tundra. When we arrive at the family’s fish traps, about 15 minutes after leaving Old Kayalivik, the Johns’ son-in-law has already gathered several Alaskan blackfish, now wriggling in a white plastic bucket. The men empty two more traps, while Bernice stoops in the grass to gather cranberries.

On our way back to Newtok, drizzle dampens our clothes. We dock on the riverbank, and Tom hauls up the bucket of fish, leading the way through the maze of muddy boardwalks to the family’s house. Tom built the humble, one-room dwelling 20 years ago with scrap wood left behind by the BIA. Now, the couple shares it with their children and grandchildren; about a dozen people cram in, with mattresses, a washing machine, a television set, and a pile of suitcases. Laundry dangles from the ceiling above a cracked linoleum floor. Tom settles onto the mattress nearest to the television set to watch football, while Bernice eats bologna and fry bread with mustard.

The longer the move takes, the worse conditions become in Newtok. It’s hard to get anyone to invest in new infrastructure for a community that is about to leave. So there are no working sewer lines, and Tom and Bernice’s family, like every household in the village, uses a “honey bucket.” They dump the waste, usually by hand, into the river. In a storm, it sometimes washes back into the village. During my visit, the water treatment plant for the village is malfunctioning.

The people of Newtok were once semi-nomadic. It was only in the 1970s, when sod structures gave way to a modern village with houses, an airstrip, and a clinic, that they became stationary. Photo by Madeline Ostrander

The slow attrition of Newtok fuels tensions in the village. By 2012, growing impatience with the pace of the move led community members to challenge the leadership of the Newtok Traditional Council, which had governed the village for 15 years. After the council refused to cede control and hold elections, the villagers organized a second council. Bernice is one of seven members of the new Newtok Village Council, and Tom works as its administrator. The BIA and other state and federal agencies have recognized it as the official governing body, but the ongoing dispute between the two councils has driven a wedge in the community. The real loss is further delay in the relocation process. When I try to contact members of the first council, they refuse to speak to me.

Modern life, with its reliance on money and bureaucracy, is divisive. Traditionally, the qasgiq gave people a center they could return to at the end of each season’s journey, explains Billy Charles, a member of the Yup’ik and a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Modern villages were organized around offices, schools, and infrastructure—not a qasgiq—and the old sod structures fell into disuse and decay. “Its loss separated the community, and there was no more collaboration,” Charles says.

For decades, the Yup’ik have faced the forces of change: the Christian missionaries who condemned and dismantled the Yup’ik communal lifestyle; the US government, which imposed different styles of organization; and policy, especially the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of the 1970s, which made native people shareholders in corporations that hold claim to land and natural resources. Now many native villages are run by a muddled set of municipal institutions, corporations, and traditional and tribal councils, with overlapping authorities. Communities facing climate change have to find ways to stitch themselves back together, even as the landscape is falling apart.

Across Alaska, warming temperatures are destroying permafrost. Winters are shorter, sea ice less reliable. Storms batter the Y-K Delta frequently and flood the coastline and rivers. In years to come, as the sea level rises, that flooding will worsen. The federal government reported in 2003 that at least 184 of Alaska’s 213 native villages suffer flooding and erosion, which is getting worse year by year. A more recent report indicates that 31 villages face dire threats, and 12 are considering relocation.

“The world is changing following its people,” says a Yup’ik adage.

When Mary John, Tom’s mother, was younger, she heard that people would cause the climate to change. I find the 79-year-old, white-haired woman bundled up in a green recliner, watching the twanging 1980 biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter. On the broken linoleum floor of her house, by the wood stove, sit bottles of yellow liquid—partly rendered seal oil, with a pungent aroma that reminds me of cheese, sweat, and old socks. Mary explains most things in Yup’ik, loosely translated by local teenager Scott Charlie and Tom’s brother, Teddy.

She speaks with a creaky voice, like the soughing of old trees, and repeats the phrase “long, long time ago,” one of the few she knows in English. Charlie passes me a plate of white rice and chewy moose meat and explains that Mary had heard that the snow would cease falling because people had stopped following nature’s laws.

Mary John—with her informal translator, local teenager Scott Charlie—remembers when her community first started warning of changes to the Alaskan tundra. Photo by Madeline Ostrander

There’s nothing romantic in Mary’s depiction of the old communities: the people “were poor. They were hungry. They had nothing.” They made coats from bird skins and boots from sealskins, ate from wooden bowls, and slept on grass mattresses.

No one I spoke to in Newtok dreams of a return to a sod-house life, and today, it would be difficult to impossible for anyone to flee the modern economy even if they wanted to. When they move this time, they will take the trappings of contemporary life with them.

As the community waits to relocate, the threat of sudden catastrophe looms. In 2005, a tempest converted the village temporarily into an island, and the next big deluge could easily engulf Newtok. The village lies 80 kilometers by boat from any place that could provide the “barest shelter” for its residents in an emergency, notes a report by the Army Corps of Engineers.

In 2008, the community hired a Fairbanks-based green-building research institute called the Cold Climate Housing Research Center (CCHRC) to design an evacuation center for Mertarvik. A young Alaskan architect named Aaron Cooke managed the project. Blue-eyed, bearded, and tattooed with a set of bands up one arm (one for each year of his life, like tree rings), Cooke dreamed of creating a set of design principles and an aesthetic customized to the rugged North. He felt that the architecture of the lower 48 had failed places like Newtok: the types of housing and heavy infrastructure that work in southerly latitudes are ill-suited to native Alaska culture and the demands of a place dominated by extreme weather.

The evacuation center that CCHRC and the community planned out would hold the entire village for at least a week in an emergency. After the community moved, it would become a gathering space, a qasgiq of sorts. Newtok residents asked for steam baths, an ample kitchen, food storage, an arts and crafts shop, and a hall for feasts and dancing. The state of Alaska gave Newtok more than $6-million to build it and took charge of the construction. But a year after work began, the old Newtok Traditional Council canceled its contract with the state and insisted the council itself would oversee the process. Construction stalled, and the state has since questioned whether the council mishandled the project’s finances. The foundation still stands at Mertarvik, unfinished.

Architect Aaron Cooke of the Cold Climate Housing Research Center has worked with the Yup’ik people of Newtok to help plan their new community and customized eco-houses. Photo by Madeline Ostrander

In 2011, the community and the Newtok Planning Group outlined a formal vision for Mertarvik. The plan is full of hopes, both simple and ambitious. It ultimately envisions a greenhouse, a big school, a new store, and windmills that spin out clean energy when the wind rushes. In these dreams, modern life and tradition become seamless and sustainable; and people adjust, even as the earth thaws, hanging on to the things that matter most: family, home, community, and culture.

Last year, the Newtok Village Council asked CCHRC and Cooke to oversee a second project, an eco-house that would combine the mobility of the past with the technology of the present. The council was inspired by an eco-house CCHRC had built in the village of Atmautluak, 129 kilometers east of Newtok, so energy-efficient that it burned less than a third as much heating oil as the region’s average home. The community asked the federal government for money to build more than 60 homes of a similar design.

CCHRC’s approach is to draw up designs and then teach locals how to build the homes themselves. The organization has worked with local foremen and crews in about a dozen remote communities across Alaska to build houses tailored to harsh environments. A rural housing authority called Tagiugmiullu Nunamiullu is doing similar work with communities on Alaska’s north coast.

“I can’t wait to see what the houses are really like,” one woman in Newtok village tells me. “I hope it’ll be a lot better than this housing that we have.”

The homes are destined for Mertarvik, but the community wanted the first house built in Newtok and moved later so everyone could share in the hopeful experience of learning about it and putting it together. Cooke was supposed to meet me in the village, where I would watch him lead construction. The design featured lightweight wooden trusses that would allow the house to be assembled quickly before freeze-up, thick energy-efficient insulation, an in-house water treatment system, and a self-contained sanitation system to separate and desiccate human waste, which could then be burned as fuel. The house would sit on a metal frame, an adjustable foundation resembling a giant double-bladed ice skate, which could be dragged across the frozen tundra or shipped by boat to Mertarvik when the community was ready. But less than two weeks before my trip, Cooke reported that weather and transportation had thwarted his plan. When I arrived, there was nothing at the house site but the building pad—a set of heavy-duty plastic mats laid across the mud and grass beside the school. Weeks after the barge carrying the supplies for the house left Seattle, it caught fire, delaying the shipment. Then storms blocked the vessel’s route through the Y-K Delta. The barge sailed past Newtok to Nome, roughly 470 kilometers north along the coast.

In the face of such setbacks, the community pushes forward with relentless optimism. More than a month after my visit, the barge returns. Frightened by the prospect of navigating the silt-choked route along Newtok’s eroded shoreline, the boat operators drop the materials for the house at Mertarvik instead of Newtok. In January, the federal government turns down Newtok’s plea for money for new houses. The planning group then receives some funding under a federal disaster program to move a dozen houses that are in good enough condition to make the journey to Nelson Island, though this will only allow the community to stage another incremental migration. Cooke plans to return imminently, now that the ice has dissipated, to build the eco-house in Mertarvik and clean up the evacuation center’s foundation, so the community can contract builders to finish it. He seems unfazed. “To work in rural Alaska, you have to have thick skin and loose ideas of what deadlines are,” he says.

Conditions in Newtok have deteriorated as the community waits to move. Between 1994 and 2004, poor sanitation caused nearly a third of Newtok’s infants to develop respiratory infections bad enough to send them to the hospital 150 kilometers away. Photo by Andrew Burton/Getty Images

It would be easy to see all of these mishaps as evidence of either an impossible conundrum or an outrageous fiasco. You could dismiss Newtok as an irredeemable place, a community and culture too outmoded to manage the demands of the 21st century. Perhaps because they have always lived at the extreme edge of the world, at the icy and squalling brink of impossibility, the people of Newtok seem relatively undaunted. Though they have already weathered cultural change so rapid it would give most others a kind of existential whiplash, they have held a tenacious grasp on their language and most of their cultural traditions. Yet society asks them to adapt again and again: to technological, economic, and legal demands that are a mismatch with the fury and volatility of the Alaskan wilderness, and to an ever-angrier atmosphere, churned up by a polluting, global economy that the Yup’ik had almost no role in creating.

It’s not clear whether our modern imaginations and technologies can enlarge enough to tackle a problem as big as climate change. From this standpoint, I wonder if the people of Newtok have an edge on the rest of us. As the world changes into something unrecognizable, this place of seals and moose, of gray rivers full of squirming fish, and of wide, frozen plains covered with geese and swans seems to ask the mind to expand, to adjust to the things you cannot force, to figure out against all odds how to find your way home.