The Unforgettable Pia Arke

Ever heard of Arctic hysteria? Neither did this Danish-Greenlandic artist until 1995, and then she forever changed the way we view Arctic explorers.

Article body copy

In the spring of 1995, Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke was digging through the archives of New York City’s Explorers Club. She was searching for maps, ethnographic images, and scientific miscellany that she could repurpose into collages that confront Greenland’s colonial past. Arke knew early 20th-century adventurers often, by turns, demeaned and romanticized her Inuit ancestors. Even so, one photo from American explorer Robert E. Peary’s collection shocked her: a native woman, topless and screaming, restrained by two fur-clad and seemingly untroubled white men. A curator told Arke the woman could have been suffering from a madness called Arctic hysteria.

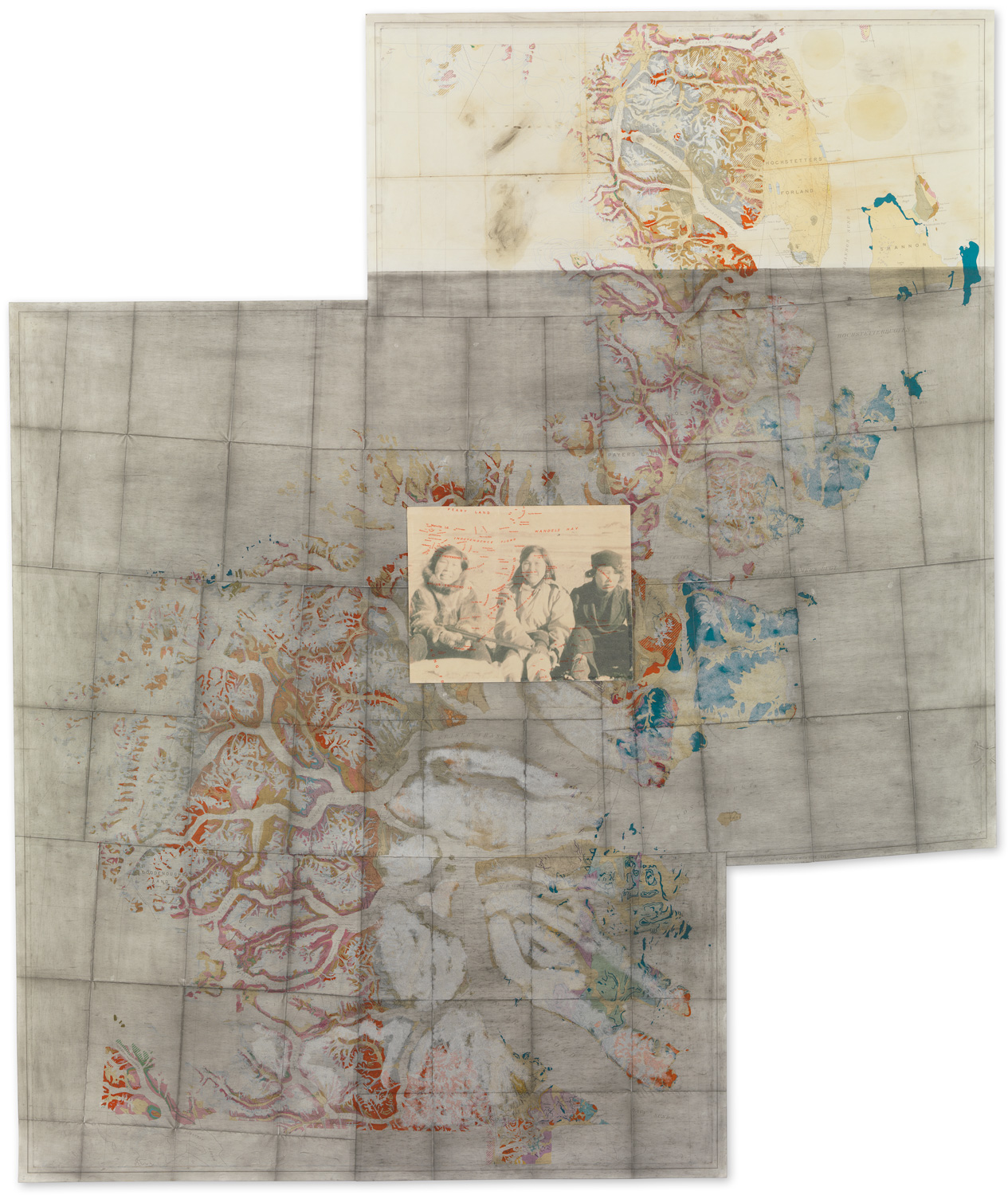

More than 20 years later, Arke’s mesmerizing film Arctic Hysteria, which she created the year after she found that dark photo, was looping endlessly in an alcove at Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Situated in a small town along the Baltic Sea about 50 kilometers north of Copenhagen, the Louisiana Museum enjoys the kind of international acclaim that makes it a dream exhibit space for most artists. Arke’s work was part of last year’s star-studded exhibit Illumination, which featured such luminaries as Ai Weiwei, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall, and Gerhard Richter. The flashiest Arke piece on display was Legende I-V, a series of five collages of Greenlandic maps and sepia-toned family snapshots layered with imported commodities such as rice, sugar, and coffee. Legende I-V is physically imposing—it dominated an entire gallery wall—and hauntingly beautiful. The foodstuffs function both symbolically and texturally, the photographs evoke the warmth of kinship, and the cartographic lines of Greenland, stamped with place names referencing colonial explorers (Peary Land, Humboldt Glacier, and Kane Bassin, for example), loom insistently over everyone.

Arke’s Arctic Hysteria is equally magnetic. The performance, which lasts six minutes, is silent and consists almost entirely of one scene: Arke crawling naked across a giant black-and-white photo of Nuugaarsuk Point, a spit of land at the terminus of a C-shaped bay. The artist lived there, outside the small town of Narsaq, Greenland, with her parents and siblings in the late 1960s. In the video, Arke strokes the artificial landscape, rolls across it, and sniffs it like an animal. Then she methodically rips the entire thing to shreds, gathers the curled shards of paper, and lets them fall across her shoulders and thighs. The intimacy of the performance and the title’s historical allusion are classic Arke.

A still from Arke’s 1996 video Arctic Hysteria shows the artist naked and crawling across a photograph of Nuugaarsuk Point in Greenland. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with funding from Anker Fonden Poul Buchard/Brøndum & Co.

It’s a bit strange to talk about “classic Arke,” since the artist, who died in 2007 of cancer at age 48, remains little known outside Denmark and Greenland. Even in those countries, Arke enjoyed only modest success during her lifetime. Although she showed her work elsewhere in Europe and scored the occasional grant, she never attracted the kind of recognition that would let her quit her day job: cooking and cleaning for the ill and elderly.

Arke might have been entirely forgotten if it wasn’t for the Danish feminist curatorial collective Kuratorisk Aktion, which organized three retrospectives of her work in 2010. One of those shows drew the attention of Anders Kold, the Louisiana Museum’s director of acquisitions. “I was both completely excited, but also slightly ashamed that I didn’t fully know the work of this artist,” Kold says. After the show, Kold contacted Arke’s heir and only child, Søren Arke, and purchased several pieces, an act that belatedly sealed Pia Arke’s reputation as a major postcolonial voice.

Arke’s favorite themes—memory, identity, and the shadows of historical violence—remain urgent, especially for Greenland. Modern Danish colonial rule, which ran from the 1720s until Greenland became an autonomous province in 1953, triggered social upheavals that still echo in high rates of HIV infection, tuberculosis, and suicide. Ironically, Greenland’s elevation from a subordinate region to an autonomous province exacted a cultural price for the Inuit. Becoming officially Danish ushered in policies that promoted industrialization, urbanization, and the Danish language. In the past 60 years, Greenlanders have slowly wrested more authority from Denmark and revived their native tongues. Even so, Greenland’s economy depends on grants from Denmark, which in turn maintains authority over the territory’s foreign affairs and monetary policy.

Artists who insist, as Arke did, on revisiting historical wrongdoings run the risk of being perceived as bitter. But if it seems like Arke dwelt on ancient slights long resolved, consider that the Explorers Club never allowed her to reproduce Peary’s unsettling photograph, even though it was at least 85 years old when she found it. The club turned her down via fax saying the image was too sensitive to reproduce. In response, Arke dove back into the archives and learned everything she could about Arctic hysteria, tracing the dark story back to its origins on the ice and, in the process, creating more truthful autobiographies of Greenland and Denmark. In her too-short life, Arke proved what 19th-century English art critic John Ruskin believed about art: that great nations write their autobiographies in a book of their deeds, a book of their words, and a book of their art, with art being the most honest of the three.

The tale of Arctic hysteria begins, in many ways, with Peary himself. In explorer lore, Peary is a controversial figure, renowned as much for his mettle as for how desperately he lusted after fame. In 1988, National Geographic published a takedown that concluded Peary had never reached the pole in 1909 as he claimed. Critics noted discrepancies in Peary’s logs and concluded that the explorer would have had to travel at an unbelievable pace to reach the pole when he said he did. But during his lifetime, Peary’s tales of North Pole pursuit and conquest electrified the American public. In 1906, 30,000 people crowded the auditorium and sidewalks of New York’s American Museum of Natural History to hear Peary lecture. President Theodore Roosevelt later gushed about the explorer’s intelligence, courage, and iron will, writing that Peary’s exploits “made all dwellers in the civilized world his debtors.”

This collage, part of Arke’s Legende I-V series, features a map of Greenland and a snapshot stamped with places named after explorers. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with funding from Anker Fonden Poul Buchard/Brøndum & Co.

Regardless of whether or not Peary reached the North Pole, he certainly got close. The successes he achieved on more than a half-dozen lengthy Arctic expeditions—including the not-insignificant triumph of staying alive—were largely due to his enthusiastic adoption of Inuit survival strategies. Unlike many earlier European explorers, Peary wore insulating and moisture-shedding furs, slept in an igloo, and traveled by dogsled. Despite his dependence on Inuit ingenuity and labor, and a professed affection for the men and women he pressed into service, Peary saw Arctic people only as primitive innocents: “keen-eyed, black-maned inhabitants of an icy desert; simple and honest, occasionally sulky; wandering, homeless people: these are my children, the Eskimos.”

Peary’s wife, Josephine Diebitsch-Peary, sometimes joined him on expeditions and once recorded a case of apparent insanity among the Inuit. In her 1894 book, My Arctic Journal, Diebitsch-Peary made a passing reference to an incident when she and her husband arrived at a seal hunting settlement at Kiatak, an island in northern Greenland: “The mistress of the remaining igloo was making an awful noise and trying to come out of her habitation, while a man was holding her back and talking to her, but she screamed and struggled so long as we remained where she could see us.” Diebitsch-Peary’s Inuit guide said that the woman was pi-bloc-to, which Diebitsch-Peary translated for readers as “mad.”

But it was Peary who interpreted pi-bloc-to, which he spelled piblokto, to the outside world. He catalogued eight episodes, offering far more detail than found in his wife’s brief account. In his 1910 book, The North Pole, Peary described piblokto sufferers as primarily female. He declared the disorder as a form of hysteria and detailed symptoms: wailing, gesticulating, pacing, imitating animals, and removing clothing. “The attack may last a few minutes, an hour, or even more,” Peary wrote, “and some sufferers become so wild that they would continue running about on the ice perfectly naked until they froze to death, if they were not forcibly brought back.” Dogs, he wrote, also suffer from piblokto.

Peary had no psychiatric or medical training, but his theory dovetailed perfectly with the field’s turn-of-the-century beliefs in the inherent weakness of the female mind and the essential primitivism of nonwhites. The diagnosis of hysteria—now discredited as sexist—exemplified the first belief; Peary’s decision, in 1897, to take six Inuit from their homes in Greenland and dump them in the stuffy basement of the American Museum of Natural History exemplified the latter.

In this context, intellectuals embraced Peary’s purported discovery of a sensational new brand of female- and Inuit-only insanity without question. The malady gained the more poetic name of Arctic hysteria and inspired scholarly speculation that would wax and wane for decades. (In academic works, Peary’s piblokto was transliterated to pibloktoq.) Psychoanalyst A. A. Brill, who headed Columbia University’s clinic in psychiatry and first translated Sigmund Freud’s writings into English, theorized about Arctic hysteria’s causes in 1913. Brill described hysteria as a childish fit thrown by a woman who does not get her way. Civilized women, he argued, suffer complex hysterical attacks or chronic symptoms, while Inuit women in the grips of pibloktoq throw more primitive tantrums: “There is hardly anything more childish than the imitation of the dog or bird, or the running away into the hills singing and crying.” For decades to come, scholars proffered their own theories about the cause: overbearing mothering, vitamin A poisoning from eating polar bear liver, insufficient calcium uptake, epilepsy, and the endless Arctic winters.

Arke’s Legende I-V was part of the star-studded 2016 Illumination exhibit at the Louisiana Museum. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with funding from Anker Fonden Poul Buchard/Brøndum & Co.

Besides the fact that Peary’s definition of pibloktoq derived from the deeply problematic notion of hysteria, it’s unclear what the explorer and his contemporaries actually witnessed. According to a 1995 article by Canadian historian Lyle Dick, Brill and future researchers defined the purportedly new disorder using a miniscule sample of secondhand reports of pibloktoq episodes. Dick argues that the term pibloktoq didn’t exist, or at the very least may not have meant what Diebitsch-Peary and her husband thought it did. Only one expedition member, Matthew Henson, spoke the Greenlandic Inuit tongue competently. Similar sounding terms have been translated in a variety of ways by different experts. While “madness” was one translation, so was “drum dance fit,” “to be in a bad way,” and “to be starving.” Dick concludes that Peary’s Inuit guides might have been naming something other than madness when they spoke, and that Peary and his compatriots witnessed a variety of behaviors that they simply didn’t understand—shamanistic rituals, anxiety, rebellion, depression, and physical illness—and categorized them all as hysteria.

Historical context points to alternative interpretations. Inuit women labored at the very bottom of the social hierarchy on Peary’s expeditions and in his camps, expected to sew, fish, carry wood, and submit to the Americans’ sexual desires. Peary, for example, fathered two sons with his Inuit laundress, Ahlikasingwah. His navigator, Robert Bartlett, viewed one woman’s hysteria as simple protest, or “pure cussedness.” Accounts described women who seemed intent on escape or dissent leaping over the ship’s railings or shouting for a knife. Expedition member Donald MacMillan recounted finding a woman named Inawaho naked and screaming, presumably unaware of her surroundings and out of her mind. But as soon as MacMillan pulled out his camera, Inawaho hurled huge chunks of ice at him and later begged him to destroy the photos. Were these women, in fact, crazy? Or were they reacting perfectly rationally—even bravely—to their circumstances?

Colonialism stalked Arke’s family for generations. Her maternal grandparents were among the first residents in Scoresbysund (Ittoqqortoormiit in Greenlandic), an exceptionally remote and rugged town in eastern Greenland that the Danish government founded in 1924 as part of a sovereignty dispute with Norway. To make their territorial claim convincing, the Danes populated the outpost with Inuit hunter families they lured from Angmagssalik (now named Tasiilaq), far to the south, with promises of limitless muskoxen herds and bountiful polar bear migrations. But hunting proved unpredictable. The relocated families prospered for a few years, then nearly starved, huddled against the cold in shoddy houses built by the colonizers. Scoresbysund survived, however, and Arke was born there in 1958, the daughter of an Inuit seamstress, Justine Piparajik Birgithe Arqe, and a Danish telegraphist, Jorgen Gant. Two years later, they had a son, Erik.

When Arke was four, the family moved from Scoresbysund to live near Thule, the American air base in northwestern Greenland. Technically, they remained in Greenland, but Inuit culture often links identity to place, and her family had left theirs. Years later, she told her friend and intellectual collaborator, Stefan Jonsson, about hosting her mother’s eastern Greenlandic relatives in Thule. “I remember lying in my bed late at night,” Arke said, “listening to them as they sat around the kitchen table, and hearing my mother speak with a different voice and in a language I could not understand.”

Arke, Erik, and their two younger siblings never became fluent in East or West Greenlandic. Their father’s job kept them shuttling between isolated outposts in Greenland and stints in Denmark. The siblings also attended boarding schools at various times; Arke studied in Hillerod, north of Copenhagen, from age 13 to 16. At boarding school, she longed for her family and the vast natural landscapes of childhood, where she and her siblings used to play among the ruins of Norse and Inuit settlements.

But Arke would make her life in Denmark. She settled in Copenhagen in her late 20s and earned a master’s degree from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. She and Erik were the first of their family to attend college, and they remained especially close; he wrote his dissertation on popular film representations of the Inuit and often contributed to her exhibit catalogs. Erik says that, as adults, neither he nor his sister felt nostalgic about Greenland. They found the idea that they should be sitting in their apartments pining for an imagined homeland to be patronizing. But Arke’s connections to Greenland permeated her work and life nonetheless.

For one, she adopted a modified version of her mother’s maiden name, Arqe, to acknowledge her maternal heritage. She also enrolled in a Greenlandic language course, but quit prematurely as the eastern dialect was not offered; Arke saw no point in learning a dialect she couldn’t speak with her own mother.

Neither Arke’s name nor ancestry shielded her from ridicule when she visited Greenland as a young woman. Language became political during the turbulent years preceding and following the 1979 referendum vote for home rule, and Arke’s inability to speak fluent Greenlandic underscored her divided heritage. “I was scolded and yelled at almost daily because I couldn’t speak Greenlandic,” Arke wrote of a 1980 trip to her birthplace. Meanwhile, in Copenhagen, Arke felt pressured to make paintings of seals and Inuit tools despite excelling at the kind of conceptual art that would eventually earn her a spot at the Louisiana Museum. She and Erik sometimes called themselves bastards—a dark joke about their divided cultural identity.

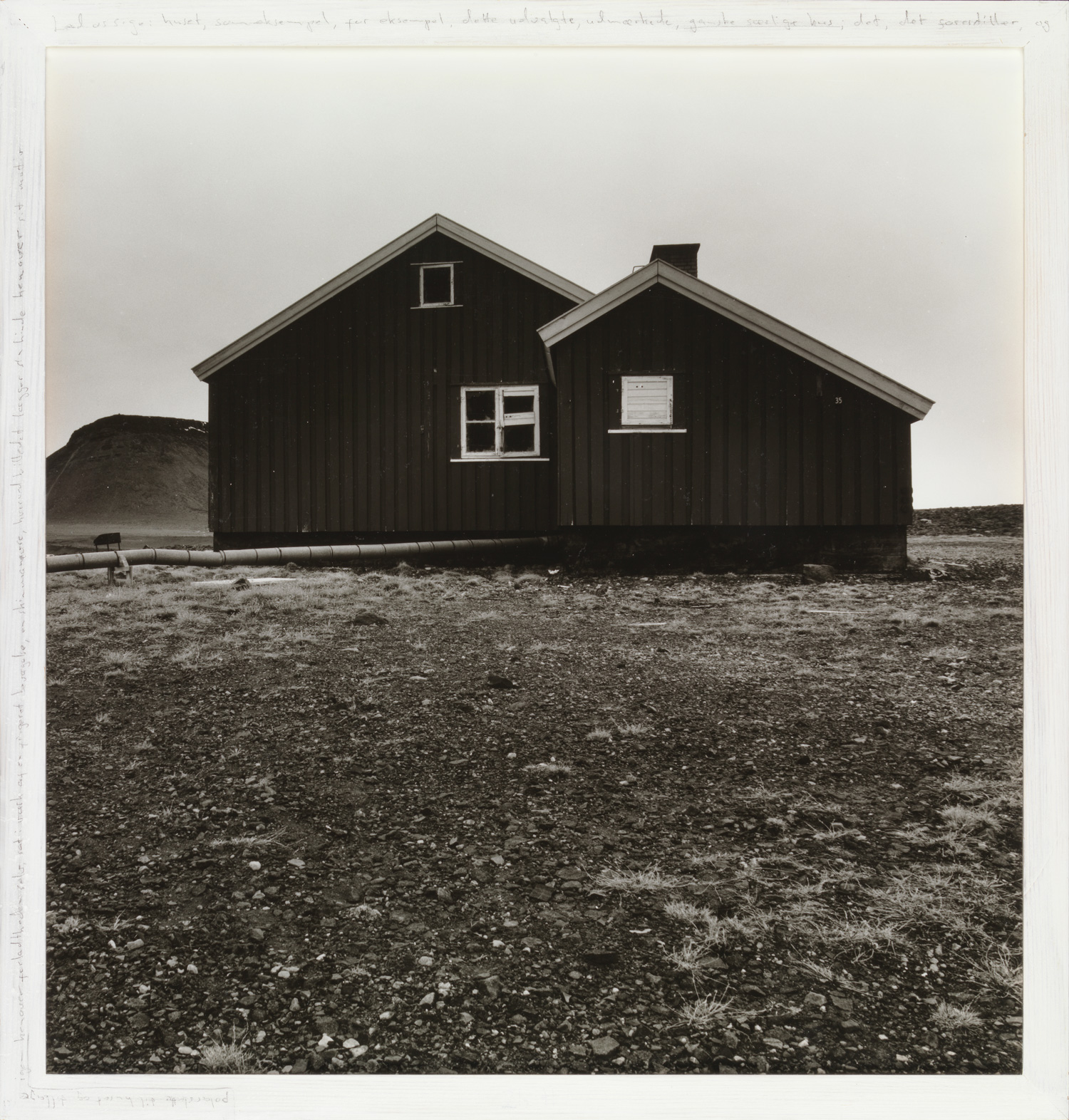

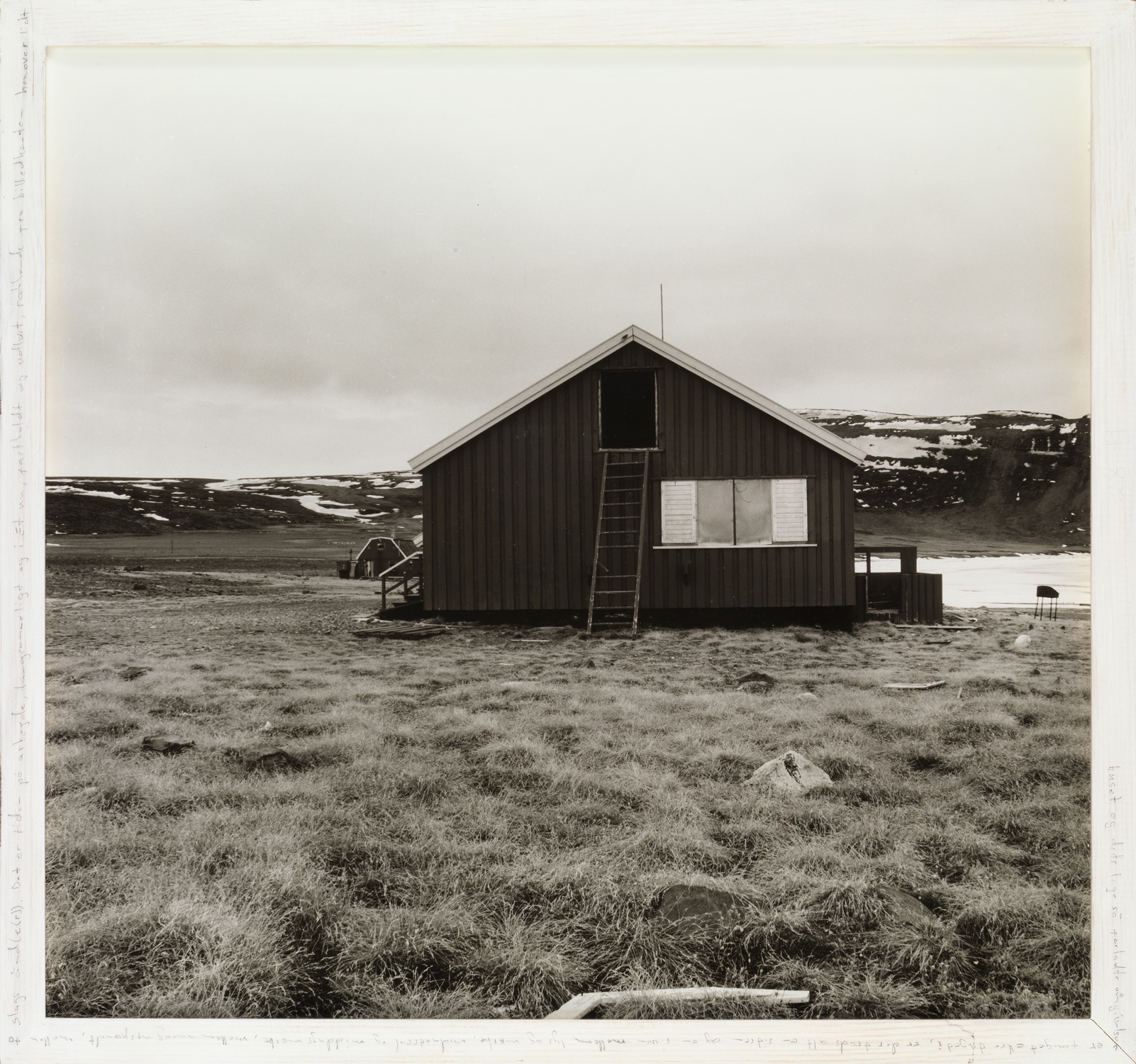

Greenland, of course, and what it means to be Greenlandic, also preoccupied Arke’s artistic inquiries. In 1988, she began thinking about camera obscuras, or pinhole cameras, a throwback to the earliest days of photography. Arke built hers from plywood, so it was big enough to stand or lie in—about the size of two refrigerators side by side. She wanted to transport the behemoth to all the places she lived as a child, but died before she had the chance. “I have always had a strong desire to revisit these places and see what has become of them,” Arke wrote. “They have a very clear language, which speaks of time, development, oblivion, and transience. They remind me of who we are. Not always in a comforting manner.”

She did ship the camera to southern Greenland in 1990, where she took the moody photo of Nuugaarsuk Point—also known as the Pointen—that appears in Arctic Hysteria. A 1996 documentary made for Danish television shows Arke and a team of helpers assembling her big white camera obscura along a windswept cliff on the Danish coast. Arke, who was then in her 30s, wore a tightly knotted scarf around her neck, a blue and teal windbreaker, and khakis—a look perhaps more unassuming tourist than avant-garde genius. But she appears in effortless command of her creation, gracefully crawling through the small hatch she used to access the interior. Camera obscuras work with a hole instead of a lens; when Arke wanted to make a picture, she’d close herself into the darkness, then uncover the hole and let light stream in to strike film affixed to an opposite wall. It took anywhere from 15 minutes for the film to expose, long enough for Arke to step into the light beam and become a ghostly presence in the final photograph. The resulting images were ethereal, as if plucked directly from dreams or memories.

This gelatin print is one of four Arke created for a series titled Imaginary Homelands alias Ultima Thule alias Dundas “The Old Thule.” Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with funding from Anker Fonden Poul Buchard/Brøndum & Co.

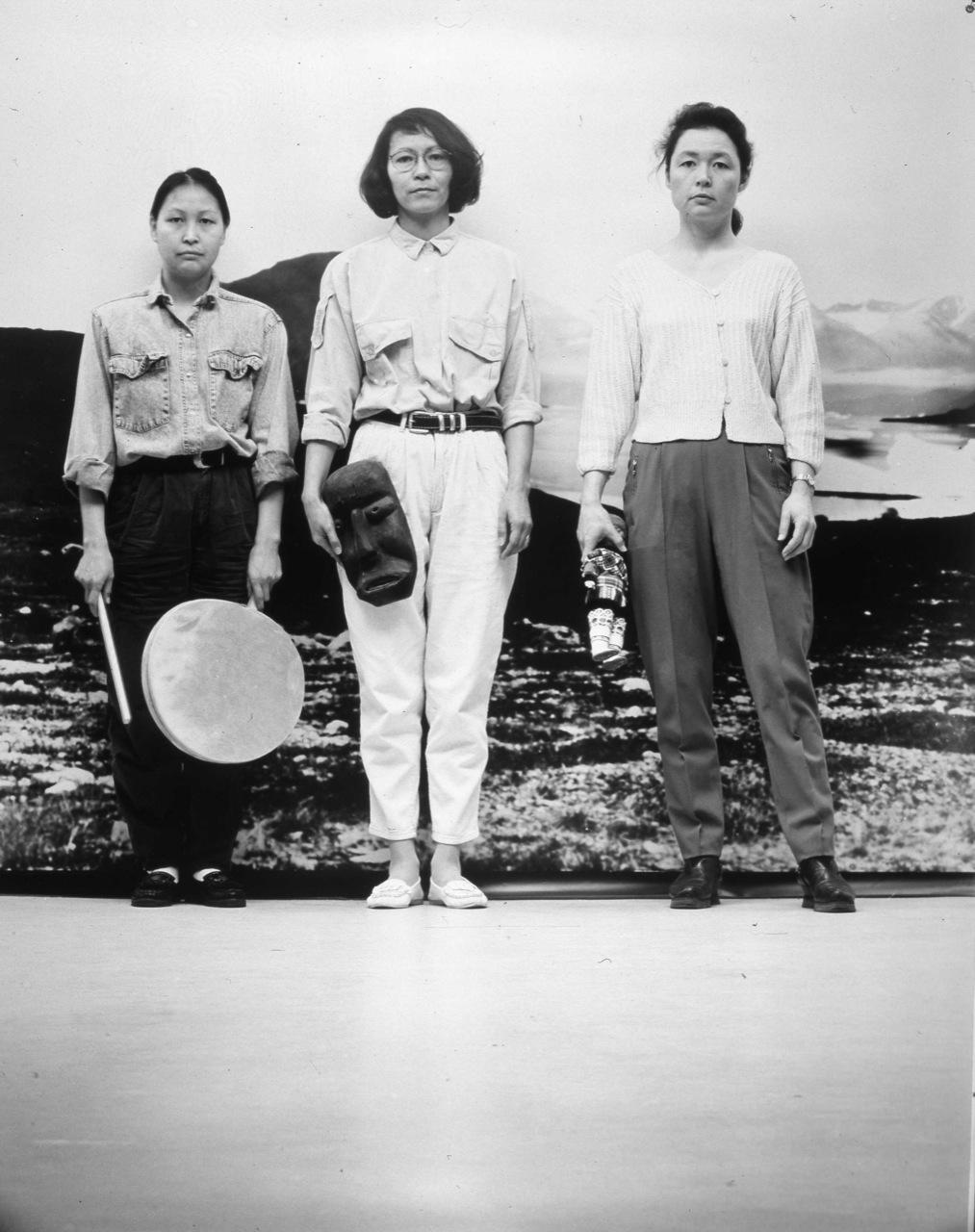

Arke also turned conventional cameras on herself, Inuit friends, and a cousin. In perhaps her most overtly political piece, Put your kamik on your head, so everyone can see where you come from, Arke posed with her back to the camera and a kamik—the traditional Inuit boot—perched on her head in a rebuke to those who would pigeonhole her as a folk artist. When Arke worked with other Greenlandic women, she shot them in black and white and frequently posed them in studios, standing not in Greenland itself, but in front of reproductions—often her camera obscura photographs—of their homeland. Her models usually appear nude or dressed in modern clothing. When Arke wielded the camera, she did so with pathos and intelligence, portraying her subjects as individuals, defined by neither their female bodies nor outsider notions of an unchanging Eskimo-ness.

Arke doesn’t explicitly invoke Peary or colonization in these images, but the subjects lurk in the background. Photographs from early explorers, which introduced the Arctic people to southerners, frequently depicted Inuit women as hysterical or hypersexual. Arke’s archival research yielded erotic nudes of shyly smiling Inuit women with titles such as Mistress of the Tupik and Flash-light study. During her exploration of Arctic hysteria in the mid-1990s, Arke created a montage called Arctic Hysteria IV, which juxtaposed those early photos, placing the erotic nudes beside shots of a fully dressed Peary and other explorers. The contrast underscores gross power imbalances, but also the ridiculousness of colonization and Arctic conquest: the men appear overwhelmed by their furs, and it’s easy imagine how ungainly they must have looked waddling along the Greenlandic coast.

“She often built her works on things she found in the archives and then manipulated them in various ways to reveal the violence of colonial history,” her friend Stefan Jonsson says. “And she did it with a sense of insistency and humor even, a kind of sad humor, and a kind of fighting spirit.” Jonsson contributed text to one of Arke’s most unusual projects, the 2003 book Stories from Scoresbysund, a sort of obsessive postcolonial ethnography and genealogy. It was Arke’s attempt to recover the lost history of the manufactured town where she was born. Arke gathered copies of more than 1,000 photos from museums and photo albums belonging to Danish descendants of the town’s first colonists and migrant workers. She then began a painstaking process of interviewing Scoresbysund’s older generations with the goal of naming every person in those images. The resulting book offers page after page of old photos with handwritten names scrawled across them. Arke found photos of her late maternal grandparents, and she catalogued Scoresbysund’s painful and sometimes shameful history. One of her discovered photos shows a young boy named Jaariussi who had been photographed in a heart-rending state of filth and neglect. Jaariussi’s father died of tuberculosis, and the boy himself died just a few years later when he fell into an ice well.

Stories from Scoresbysund chronicles colonial tragedies, but also includes less black-and-white instances of cross-cultural entanglement. In one chapter, Arke writes about her half-brother, Ole Brønlund, her father’s unacknowledged child. Brønlund lived a sort of parallel life to Arke’s; he represented what might have been had she stayed in Scoresbysund. He spoke Greenlandic, of course, and was an accomplished hunter before economic necessity drove him to paid work. She writes about Brønlund with affection and curiosity, and not a hint of bitterness toward her father.

Arke’s series Imaginary Homelands alias Ultima Thule alias Dundas “The Old Thule” was created between 1992 and 2003. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with funding from Anker Fonden Poul Buchard/Brøndum & Co.

Arke’s longtime friend Kirsten Thisted says Arke understood that colonialism represented not only subjugation, but also exchange, especially on human levels. Thisted, a University of Copenhagen professor of cross-cultural and regional studies who has written extensively about Arke, recalls attending a Copenhagen art opening featuring a young Danish man who had traveled to Greenland, fallen in love with an Inuit woman, and made her his muse. Thisted and her friends hated the show; they thought it was exploitative. “But Pia loved that work,” Thisted says. “She said, ‘No, it was personal. It was sincere.’ Instead of just doing what was easiest and saying, ‘No, I’m a Greenlander,’ or ‘No, I’m a Dane,’ she was insistent on being both at the same time, insistent on not having to choose and on being able to see people as human beings.”

Arke kept working, exploring artistically, what it meant to live in that in-between space until cancer treatments wore her down in the mid-2000s. She apparently chose not to document her own illness, although photos taken by others show her lovely round face puffy and transformed by sickness. Before Arke died, she returned to Scoresbysund with a handheld camera and began recording. In some of the footage, Arke can be seen in the wheelhouse of a boat with her half-brother, chatting and gazing at the Greenlandic coastline. Her intentions remain unknown, but it seems nearly certain that her video project wouldn’t be a straight documentary, but rather something more oblique, something attuned to the absurdity of the human condition.

After all, it’s absurdity that’s at play in Arctic Hysteria. Almost everyone has a different take on the meaning of those six minutes: Arke’s revolting against stereotypes of Greenland and Greenlandic women; she’s suggesting that the notion of an idealized and unchangeable Arctic is itself insane; she’s using a grotesque humor to demonstrate that she doesn’t belong. The ambiguity is part of the work’s strength. The Danish writer Mette Moestrup describes Arke as a “hardcore thinker.” But her brother Erik urges viewers not to conflate intellectual rigor with detachment. “There are very few people in eastern Greenland,” he says. “So whenever there is an ethnographic photo showing natives from eastern Greenland, it would also be our family. It’s our family, there’s no circumventing that.”

Those women that Peary called crazy? Arke considered them kin. That sad knowledge drove all of her work, even the high-concept Artic Hysteria. “I make the history of colonialism part of my history in the only way I know,” Arke once wrote, “namely by taking it personally.”

Psychiatry has, thankfully, come a long way since Peary’s time. The field no longer argues that indigenous peoples suffer from special forms of madness, instead acknowledging that all diagnoses take place within a cultural context. Pibloktoq itself has drifted into obscurity, so much so that when the disorder quietly disappeared from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the field’s diagnostic bible, three years ago, barely anyone noticed. The fight over what’s remembered and what’s forgotten is far from over. Arctic hysteria—and Arke—beg us to remember.