Art and Accounting in the Age of Whaling

Hand-carved stamps helped whalers keep track of their catches and assess the success of their voyages.

Article body copy

“Can you see anything?” Henry Carter was asked in 1923 as he peered into King Tutankhamun’s tomb. “Yes,” he replied, “wonderful things.” This column explores other wonderful things—intriguing artifacts or technologies that give insight into coastal cultures.

Henry Clay Murdock’s entry in the logbook of the whaling ship Nassau on June 14, 1852, began, predictably, with the weather. It was foggy and the visibility was poor that morning near the Gulf of Anadyr in the Arctic, but still a cry came out from atop the masthead: whales ahead. The deck erupted in activity, and throughout the morning sailors lowered whaleboats and pursued the monstrous prey.

The crew was swift and skilled; after all, they’d been sailing the world’s oceans in pursuit of whales for almost two years. During that day and into the next, they caught three whales, which they chained alongside the Nassau and began “cutting in”—removing strips of blubber that could weigh upwards of a tonne with long-handled cutting spades. To complete his journal entry, Murdock took a wooden stamp carved in the likeness of a bowhead whale, dipped it in ink, and stamped three whales below the day’s notes.

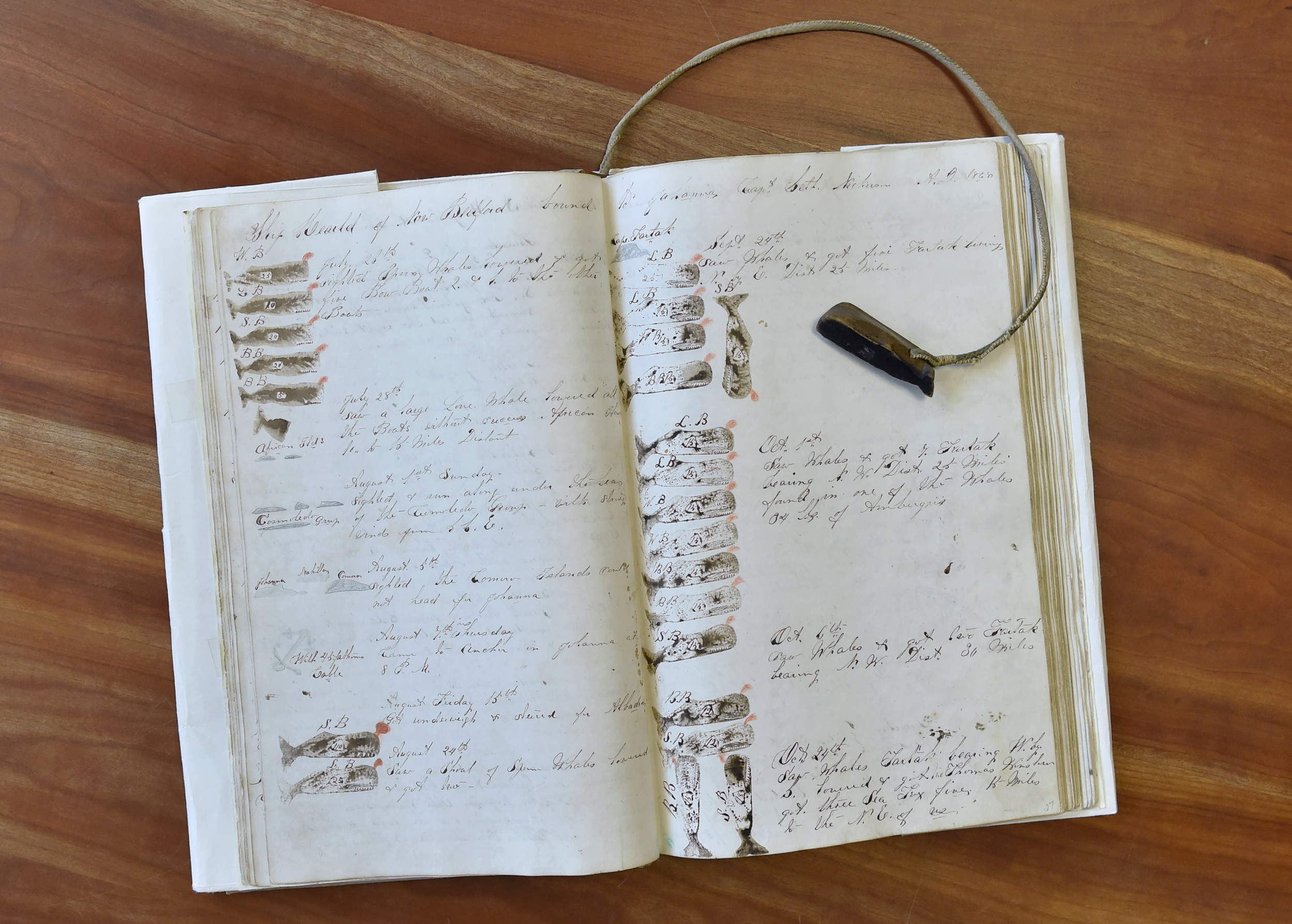

It is difficult to find a logbook and the whale stamp used within it. One exception is this log kept by Frederick Howland Smith, to which he tethered a carved stamp used to record the catch. Photo by Nelson Mare

Murdock’s use of a hand-carved stamp to record whales caught wasn’t just a passing whimsy of a creative—or bored—first mate. The stamps served a very practical purpose for the whaling ships working out of New England. After the War of 1812—as the United States established itself as a sea power with full rights to trade on the open ocean—keeping track of maritime industries was paramount, explains Michael Dyer, senior maritime historian at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts. As the whaling fishery expanded, vessel owners needed solid data: where whales were taken and when, the size and species, as well as the number of barrels of oil rendered during a voyage. “It’s super tedious to go through the logbook to find out when somebody killed a whale, so it’s a lot more efficient to make a mark,” says Dyer. “The stamp was a very efficient way, at the end of the voyage, to go through [the logs] and to collate the success of that voyage.”

A page from the log kept by Henry Clay Murdock, mate of the whaling ship Nassau, shows how he used carved whale stamps to depict the whales caught in the Arctic in June 1852. Image ODHS#614, Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA.

Using the stamps, a ship’s owner or his agent could scan the logs to quickly tally whales seen (usually denoted by a stamp of a whale’s tail flukes) and killed (a stamp showing the full body). Marginal notes as to whether it was a bull, cow, or calf, and details such as “sunk,” “cut adrift,” or even the gruesome “lost spouting blood,” were also often included. Some ships had a collection of stamps, one for each species they’d predictably see, most often bowhead, sperm, or right whales. As well, many of the stamps had a small space where the mate would later record the number of barrels of oil derived from each catch. (By the 1760s, most American whaling ships had ovens called “try-works” installed on deck, enabling them to boil whale blubber at sea, rendering it into oil that would be stored in barrels. “This is one of the technologies that really set the stage for American dominance in whaling,” says Dyer.) The whales caught by the Nassau crew on June 14 yielded 100 barrels of oil each, as Murdock would later note in the log.

It’s likely that Murdock carved his own stamps, but anyone on board could do so with the right supplies. And not much was required. Most stamps were carved of wood, although bone and ivory were also used. Some stamps were multisided with two or three images on one implement; others had embellished handles or even spinning mechanisms.

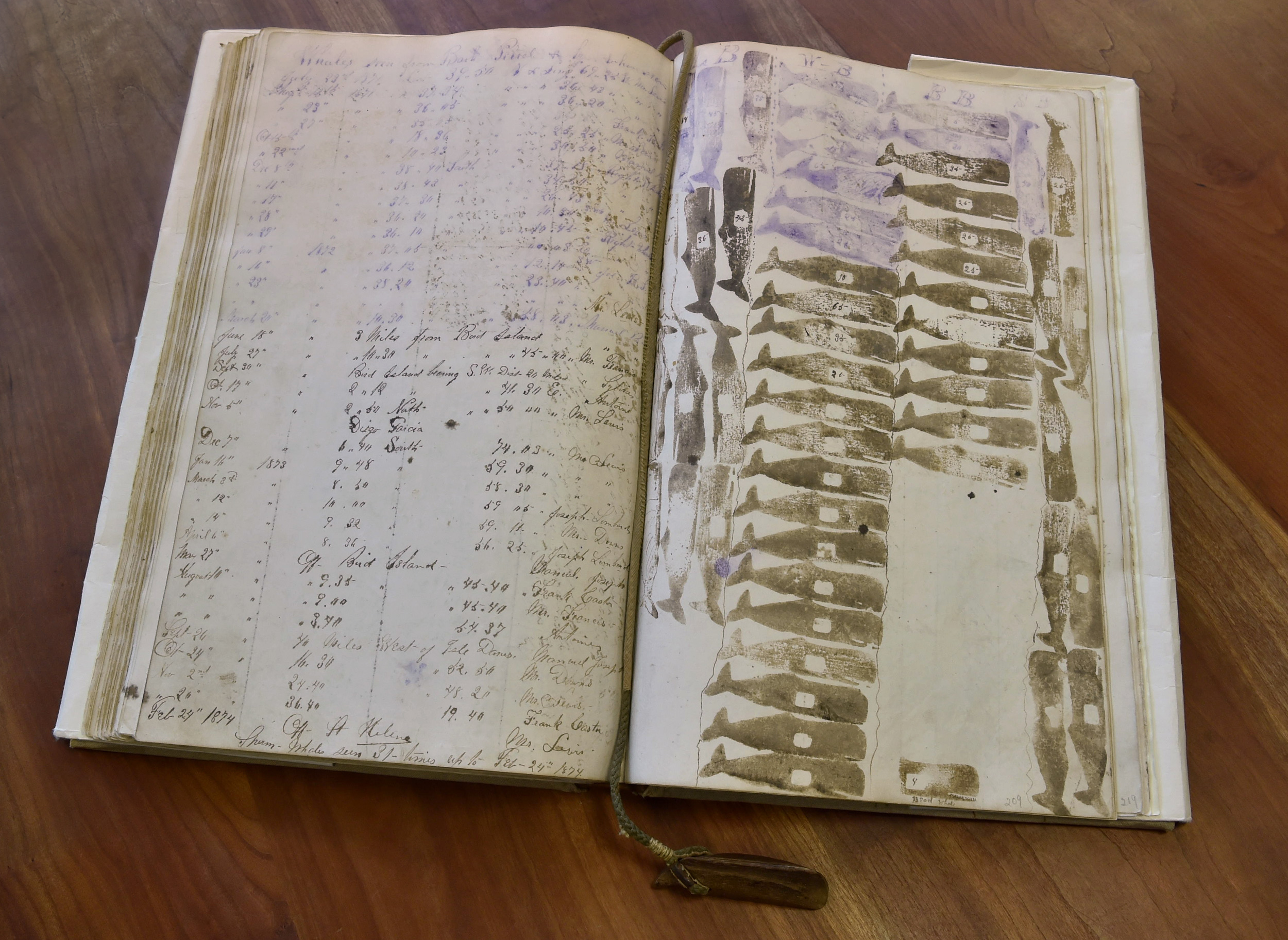

Techniques for recording whale hunts varied between ships. This record by Frederick Howland Smith tallied the total whales successfully harvested during the voyage, rather than making a stamp on the particular day a whale was caught. Photo by Nelson Mare

One of the most stellar examples is a box of seven stamps held at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Along with stamps of a sperm whale and a whale’s flukes, are two ships: a three-masted bark, and a schooner. The bark would be used in the journal to indicate a ship seen or spoken to, Dyer explains. As vessels passed one another, the captains would use their speaking trumpets to holler things such as their ship’s name and homeport, how long they’d been at sea, and how many barrels of oil they had on board. That information would then be written into the daily record. The schooner denotes a pilot boat, the smaller ships used to guide a whaler into port. Dyer thinks the stamp of a small, unidentified cetacean would be used to note other ocean life, probably other whales, but the sunfish stamp is more of a mystery. Dyer has pored over dozens of logs for his forthcoming book, Art of the Yankee Whale Hunt, and notes that manta rays and sunfish are common in journals. “I don’t know why … they’re just ugly and weird,” he says. His interpretation of the seventh stamp in the collection is less ambiguous though: “The coffin indicates a dead guy.”

Today, many of the logbooks preserved in museums, archives, and private collections include stamps, although their use certainly wasn’t standardized or ubiquitous. “Plenty of logbooks have no stamps in them,” says Dyer, adding that to get any data out of the stamp-free books, owners would have to comb through them, page by page, entry by entry.

Note the “cut out” in the sperm whale stamp in this collection. When the stamp was used in the log, the mate would record the number of barrels of oil rendered from that particular whale in the space. Photo by Nelson Mare

Compared to many logs, with crimped, illegible text, Murdock’s logbooks must have been a relief for anyone, including contemporary archivists and historians, trying to glean information from them. His prose is fairly clear despite the dearth of punctuation and capital letters, and his entries are all business: short and to the point. A few of Murdock’s contemporaries, however, elevated the whaling vessel journal to an art form. Most outstanding are the logs of Washington Fosdick, mate on the Saratoga. He lavished his script with flourishes and curlicues and meticulously recorded whale captures, but he also embellished the margins with detailed sketches of ships seen en route as well as profiles of islands, mountain ranges, and the occasional human community.

While the journals of Murdock, Fosdick, and others speak to a trait that is inherently human—the will to create art, even for the most mundane of tasks—it also speaks to a fundamental tenet of modern business: data is king.