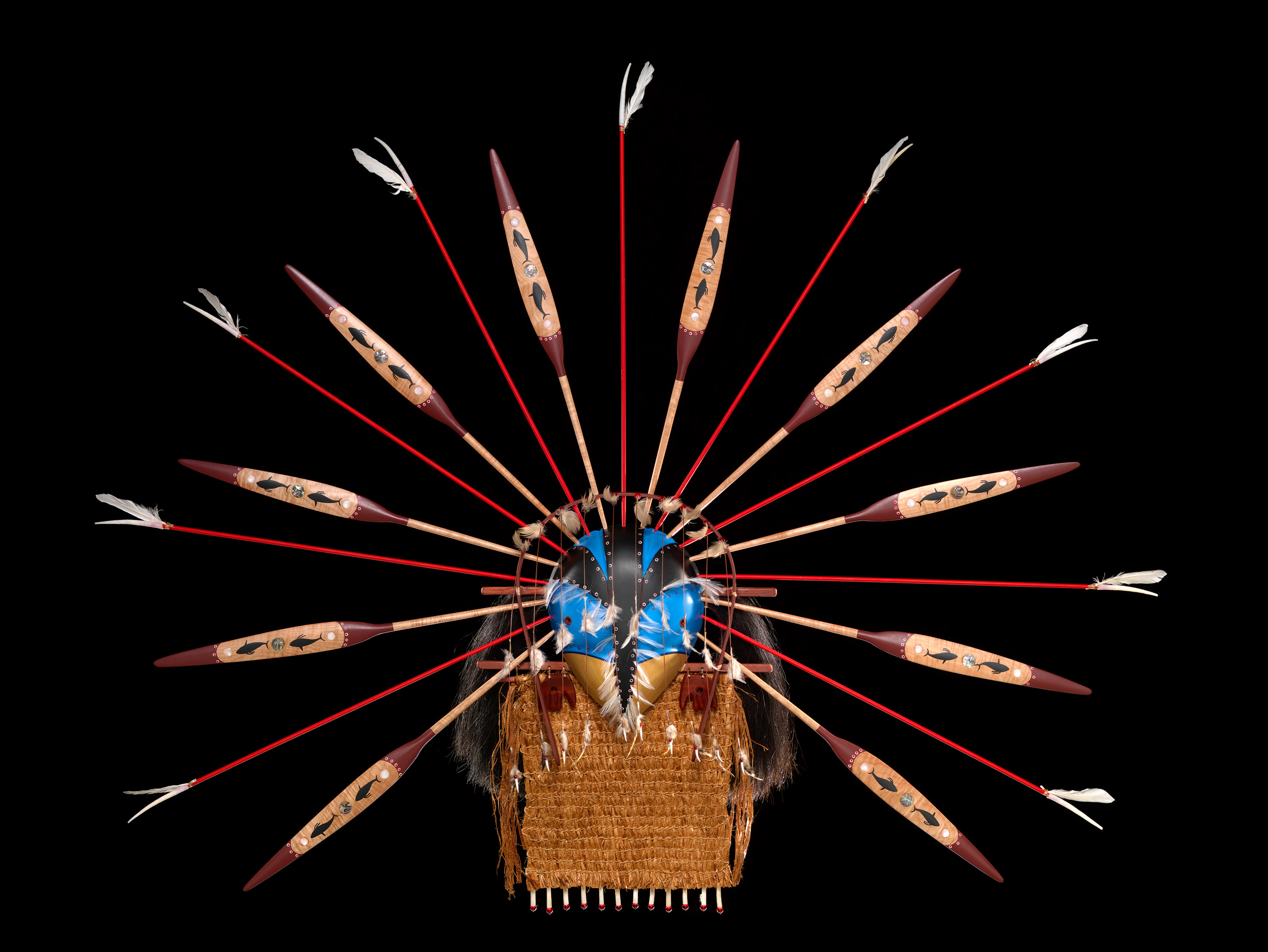

It’s a Bird, It’s a Mask, It’s Puffin Man!

The past and future are in full flower on Kodiak Island as an indigenous culture reclaims its artistic roots.

Article body copy

“Can you see anything?” Henry Carter was asked in 1923 as he peered into King Tutankhamun’s tomb. “Yes,” he replied, “wonderful things.” This column explores other wonderful things—intriguing artifacts or technologies that give insight into coastal cultures.

It was winter. Jerry Laktonen was standing outside a friend’s house staring at the well-stocked woodshed, his gaze gripped by a chunk of red cedar. Raindrops split the air, as they do at that time of year in the moist Pacific Northwest.

Laktonen is a Sugpiaq/Alutiiq artist from Kodiak, Alaska. To this carver of masks, the red cedar bound for the wood stove conjured a face from his ancestral past and his modern upbringing—a puffin superhero. Laktonen turned the red cedar into the face of the mask he calls Puffin Man, Alutiiq Superhero.

Puffins were a Sugpiaq/Alutiiq cultural staple. Dancers wore bracelets and anklets of puffin beaks, and feathers adorned clothing. Masks provided a way for storytellers to pass on traditional tales and histories, and to communicate with the spirit world, a custom echoed in Laktonen’s modern creation. Hands hanging down on either side of the face bear holes, and represent an opening to the non-corporeal beings of the sea and sky. The 10 paddles radiating from Puffin Man’s head are a stylistic nod to long-ago Sugpiaq/Alutiiq artists. For Laktonen, the adornment honors the most important tool for a mobile community of hunters, gatherers, and fishers. “The paddles symbolize that the puffin is moving really fast,” Laktonen says. “It’s also about paddling into the future.” The wool cape is de rigueur, since Puffin Man is a superhero. (The piece’s subtitle is pure Ghostbusters: Having bad dreams? … Kayak leaking? … Who you gonna call?)

Twenty years ago, when Laktonen was 45, he quit commercial fishing and began carving paddles, quickly moving on to masks, almost immediately launching the Puffin Man series. “I wanted to make a piece to express my feelings about starting out in the art form of the [Sugpiaq/Alutiiq] people in Kodiak, it was kind of my coming out party,” Laktonen says. Puffin Man, Alutiiq Superhero is the last in the series of 12 masks, sporting similar features, some with capes, some without.

For much of the modern era, the words “art” and “Sugpiaq/Alutiiq” were seldom, if ever, united. The vanguard of the age of exploitation landed on Kodiak Island, with Russians wading onto its shores in the fall of 1784, followed by the Americans a century later, lured first by the luxurious fur of sea otters, then by fishing grounds fat with salmon. Unlike nearby indigenous groups—the Y’upik and Tlingit, for example—the Sugpiat/Alutiit nearly lost their culture. What remained was literally underground. Until it wasn’t. Beginning in 1983, and spanning about 12 years, archaeologists unearthed a hidden civilization, the Sugpiat—a name Russians almost erased when they dubbed the inhabitants they encountered the “Aluet” people.

Though people have lived in the region for the past 7,500 years, it was the Sugpiat of an era dated to 650 years ago who gave the culture back to their descendants. The Sugpiat of that era lived in sod houses along the Karluk River, from the estuary to Karluk Lake, 35 kilometers inland. Archaeologists began an excavation at the river’s mouth. The site, Karluk-1, astonished the researchers. One student remarked that it looked “as though someone opened the bottom of a museum and shook it out all over the beach.”

Digging with shovels, trowels, and their bare hands, the archaeologists sifted through each layer, revealing whispers of bygone times: wooden masks and toys, baskets, and even preserved blades of grass. When they reached the dark soil of house floors, they smelled seal oil. Archaeologists collected over 26,000 bits of the past, a fraction of which is displayed at the Alutiiq Museum on Kodiak Island.

Karluk-1 was key to the revival of Sugpiaq/Alutiiq art, says Sven Haakanson, a University of Washington anthropologist, former executive director of the Alutiiq Museum, and carver. This once-hidden art jolted the community. “Wait a minute, we had masks on Kodiak? We had all these other things? Where are they?” Haakanson recalls thinking. “For us, these are the Picassos and Rembrandts of our ancestors.”

In a way, the artists were hidden as well, but the museum collection lured them out of their latency. Many burgeoning artists, including Laktonen, visited the museum to study the work of their ancestors. The memory of the Sugpiat at Karluk-1 sparked a cultural renaissance. “It’s who we are today,” says Haakanson, who is currently at work on two masks: a pig mask for his pig-loving daughter and a Viking-era mask inspired by his Danish ancestry, each emerging from the wood with Sugpiaq/Alutiiq form lines.

Laktonen has been incorporating basketball hoops into his latest work, an allusion to the hoops embellishing some Sugpiaq masks. Laktonen readily acknowledges his thoroughly modern approach to art; he needs to make a living and from the beginning he has wanted his art to be relatable. “Puffins are loveable, cute animals and I think everybody who sees them enjoys them. So in a way, I’m a shameless marketer.”

Yet, with that hunk of wood, Laktonen performed an act profoundly artistic and beyond temporal and cultural boundaries: he made something out of nothing.