Fast Bird, Slow Food

In New Zealand, sooty shearwater populations are being restored with the collective knowledge of Māori harvesters and seabird researchers.

Article body copy

Under a scorching December sun, elders of the Māori group Ngai Tāmanuhiri sing an incantation. A dozen people, each clutching a cardboard box from a fast-food restaurant, begin a short climb up the steep hill at Longbush Ecosanctuary on Te Ika-a-Māui, New Zealand’s North Island. As the singing fades, the hikers arrive at a hilltop barricade and pass through a padlocked door. The group is comprised of representatives of Ngai Tāmanuhiri, conservation trusts, or government agencies. The precious treasure in each takeaway container is a young tītī, or muttonbird, that is about to be released into its new home: a predator-proof, purpose-built—and very pricey—breeding colony.

It is ironic that the tītī are carried in fast-food containers. Admittedly, they are fast. They have been clocked at speeds of up to 159 kilometers per hour as they travel some 64,000 kilometers round trip from their feeding grounds in the northern hemisphere to their breeding habitat in the southern hemisphere. And while the chicks are also food—and have been a staple of the Māori diet for at least 700 years—tītī embody all three principles of the “slow food” movement: good for those who eat them, for those who harvest them, and for the planet. They also offer a slow return on investment. Once the birds released at the Longbush breeding colony fledge and leave their artificial burrows, it could be seven years before they return to lay their first eggs.

That a seabird is deserving of such care, expense, cooperation between diverse groups of people, and the blessing songs of elders speaks to its cultural and ecological importance. While tītī are seemingly ubiquitous—most recent estimates of 21.3 million in and around New Zealand make them one of the most common seabirds in the Pacific—they are in a steady decline and are rated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as “near threatened.” Concern about the survival of the sooty shearwater (as it is know elsewhere in the world) and its continued presence on the landscape and in Māori culture has brought together a cadre of people who have blended traditional knowledge and modern scientific practices to forge a future for the species.

Sooty shearwaters use their long, stiff wings and a particular flight technique to fly close to the water’s surface, seeming to “shear” across the waves. They feed at the surface or dive as deep as 60 meters to capture fish, squid, krill, and even offal cast behind fishing boats. Photo by blickwinkel/Alamy Stock Photo

At Longbush, Ngai Tāmanuhiri member Richard Brooking recounts how a century ago, this hill would have been riddled with the burrows of breeding tītī. But here, as across much of New Zealand, tītī populations succumbed to cumulative assaults as changing land uses and introduced species—from stoats and rats to feral pigs and cats—played havoc with their population. The more recent declines have been exacerbated by global factors such as climate change, overfishing (which depletes the tītīs’ prey), drift net and longline fishing (which snares the birds as by-catch), and all forms of pollution, but restoring the breeding colonies is one local action with proven success.

Until they fledge in about a month, the facility’s predator fence will keep the chicks safe. Project volunteers will routinely feed the chicks and check the colony for interlopers. If all goes well and the chicks return as breeding adults in five to seven years, a population of tītī could re-establish here. But it’s slow going. At the rate of one egg per mating pair per year, scientists estimate it will take 50 years for this reintroduced colony to reach historical levels and be safely harvested under a Māori stewardship system called kaitiakitanga.

Working to re-establish decimated populations is one facet of kaitiakitanga, but so is the deliberate harvest of the birds, which can be sold, bartered, or kept for personal use. Tītī colonies on Te Ika-a-Māui disappeared a century ago, but while Brooking and his colleagues are tucking tītī chicks into their artificial burrows at Longbush in an attempt to reverse this situation, Māori birders on the 36 Tītī Islands (the islands around Rakiura [Stewart Island] at the southern tip of the country) are gearing up for a 10-week muttonbird harvest. These islands have remained tītī strongholds for generations by virtue of geography and effective traditional management practices. Today, over half of New Zealand’s sooty shearwaters breed in this island group where local “birders” (the name for the harvesters) keep a sharp eye on the population.

In the heart of the Tītī Islands, Donald Bragg, a Rakiura Māori birder, shares his love of the birds and their entwined cultural history. “When you work with these birds and see them up close, you have a soul connection,” he says. Bragg descends from one of the original Rakiura Māori families of the island Te Poho o Tairea. His great-grandmother, Waa, was a Māori birder who managed a manu (birding territory) with her husband, a ship’s blacksmith from Connecticut, and their extended family. Like most of the Rakiura Māori with these rights and responsibilities, Bragg’s lineage is carefully recorded and his family’s participation in the manu is tightly controlled. Unless harvesting protocols are followed, rights to harvest tītī are lost. The families prohibit all access to the island except to their own members and they restrict their own access to a very limited time starting in the middle of March. Then, to get ready for the season, they trap predators, repair unoccupied burrows, and prepare the paths, called “tracks,” that harvesters use to access the colony. Staying to the established tracks ensures a fair allocation to the families as well as conservation of the colony since the nests that are out of reach go unharvested. As Bragg says, “We work with Mother Nature. If you’re taught right, sustainability will follow—it even reflects in the condition of the birds.”

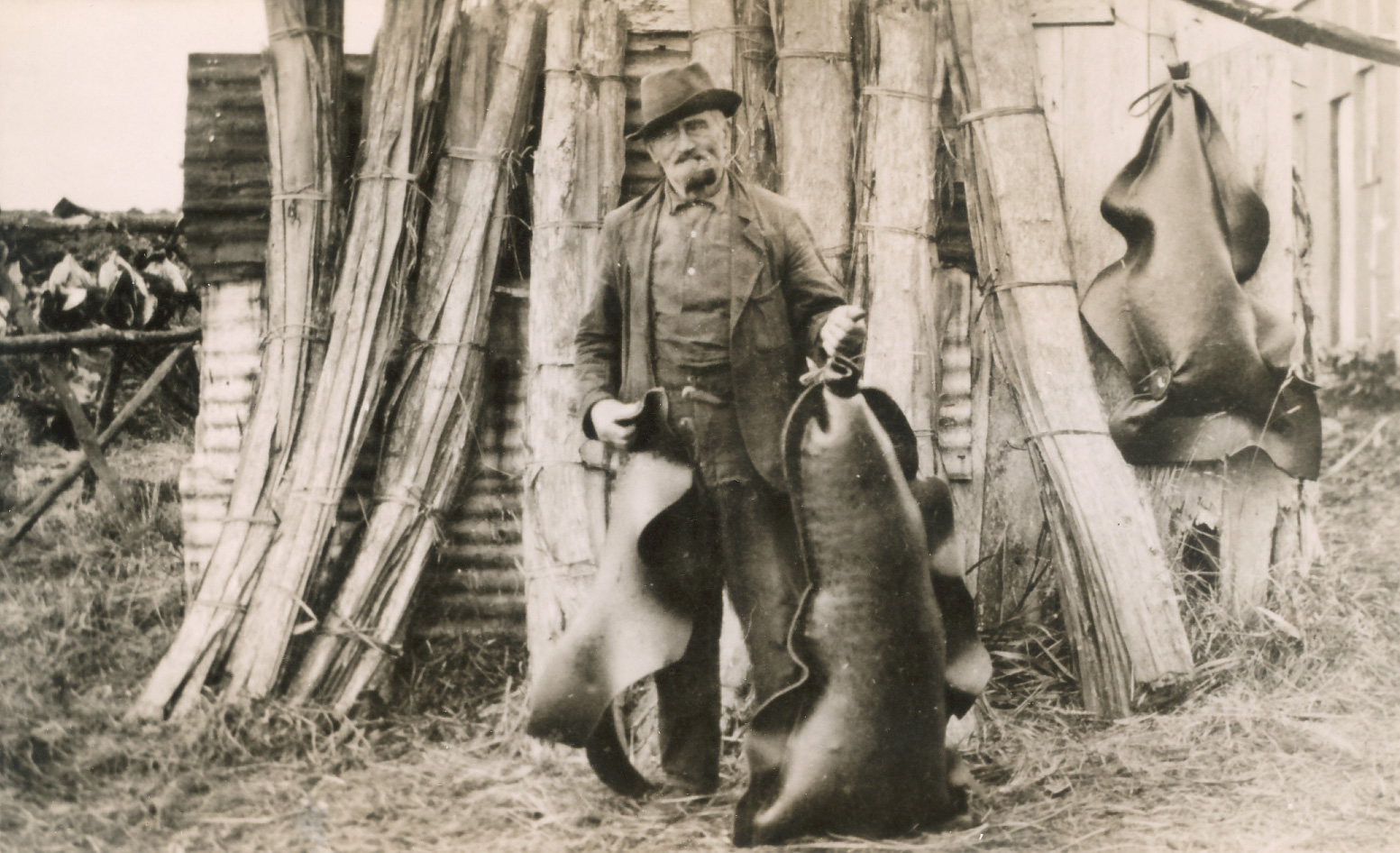

John Kaiporohu Bragg, Donald Bragg’s grandfather, in 1920, on Tia Island, New Zealand. He is holding traditional pōhā, bags made from bull kelp, in which newly harvested tītī were stored. Photo courtesy of the Stewart Island Museum

The birds are harvested in two stages: nanao, during the first three weeks of April when the chicks, rich with omega-3 oils, are pulled from the burrows; then rama, from the last week of April to mid-May, when the chicks are captured on the tracks at night as they’re preparing to fledge. (At this stage, the birds are leaner, but meatier.) The birds are carried to processing huts where they’re plucked and waxed, gutted, salted, and packed around 20 to a bucket. (Instead of buckets, some people opt to use traditional bags fashioned from a large species of kelp packed into flax baskets.)

On each island, most families participate in collectively setting allocations for their region and overseeing management concerns, which increasingly relate to declining tītī populations. For the Māori, the implications of losing this food source and a valuable industry reach beyond revenue—the harvest is a key cultural practice that fits into an evolving mātauranga, a worldview based on traditional ecological knowledge. In the early 1990s, the Rakiura Tītī Islands Committee joined researchers at the University of Otago to determine why tītī were declining. The result was Kia Mau te Titi Mo Ake Tonu Atu, the Keep the Tītī Forever (KTF) research project, which blends the traditional knowledge and expertise of the Māori with scientific study to determine, among other goals, whether traditional harvesting practices are sustainable, given declining populations. For more than 20 years, the project has operated on many research fronts, from tracking damage caused by invasive predators at breeding sites to monitoring tītī by-catch in fisheries.

One invaluable source of information for the project is the Rakiura Māori muttonbirding diaries, which record generations of harvesting information. Zane Smith’s family, for example, has a collection of diaries that provide a wealth of information on the natural history of tītī populations on his family’s Herekopare Island manu. The family has kept muttonbirding diaries since the 1970s and Smith continues to add entries each year, recording the harvest and other observations, such as the condition of chicks or occupation of burrows. “[2014] was a shocker,” says Smith. “Hardly any burrows had birds.” The long-term data from the diaries helps determine trends and natural oscillations. When tītī numbers are low, in keeping with kaitiakitanga, the intensity of harvesting is deliberately not increased and fewer birds are harvested. According to Bragg, 2015 was much better: “They fed well and lots flew, which made it a very good season.”

Sooty shearwaters spend most of the year feeding at sea and only come ashore to breed. A breeding pair builds a nest at the end of a long burrow and raises a single chick. Photo by Frans Lanting Studio/Alamy Stock Photo

The KTF project is studying whether adjusting the harvest can compensate for losses caused by things out of the harvester’s control, such as reduced food supply at sea. The published research of the KTF team, which includes researcher Corey Bragg, Donald’s nephew, shows the traditional rate of harvesting oscillates around an average of 18 percent of chicks annually, a rate that has sustained the traditional food system for well over 700 years. Their research even found that population declines have been slower on the four islands where the Rakiura Māori maintain a traditional harvest compared with three islands where the birds are not harvested. The cause isn’t entirely clear, but stewardship practices such as predator control undoubtedly play a key role in compensating for harvesting pressures. Still, to mitigate the losses from global factors, the research suggests reducing the intensity of harvesting from a quarter of manus as one practical way to increase the tītī’s chances. Smith notes that his family is already inadvertently doing this by limiting the harvest to the rama period when they get better meat.

While careful harvesting and care of the manus, as well as reintroduction efforts like the one at Longbush, make a difference, so much of the decline in tītī population is out of the hands of New Zealanders. To look beyond the country’s shores, researchers from the KTF project also track the birds at sea to understand their migration and feeding behaviors. The results show that steep population declines were mitigated somewhat once drift nets were banned globally in 1992, but have continued on a slower, but still worrying, downward trend of one to two percent annually. The ultimate impact of climate change and other broadscale environmental challenges continues to be monitored.

With a bird so inextricably entwined with a community’s diet, culture, and livelihood, the Māori press for action on conserving sooty shearwater populations. Meanwhile, their investment in research, predator control, burrow management, and advocacy is proving a vital force in seabird conservation. As Smith notes, the motivation to save the tītī is so much more than just protecting a food supply, it is protecting a way of life. The re-establishment of colonies at Longbush Ecosanctuary on Te Ika-a-Māui, is the surest signal that this is a community invested in the future of its culture, restoring hope one burrow at a time.