Guardians of the Coast

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing, but British Columbia’s coastal First Nations are joining forces to safeguard the coast.

Article body copy

Skipper Bob Martin strides through the cabin and, before stepping up to the controls to ease the Northern Lights away from the dock, turns back to the group: “Don’t forget,” he says with mock solemnity, “you guys signed peace treaties, so no one’s going to kill each other on the boat down there, right?” Four Haida men chuckle as they duck into the cabin from the stern.

“Not yet—the day hasn’t started,” one of them retorts.

They greet the two men from the Tsimshian community of Metlakatla—located just northwest of us here in Prince Rupert, on British Columbia’s north coast—already on board before sliding into upholstered bucket chairs. Ross Wilson, a member of the Heiltsuk First Nation who works for the Metlakatla Stewardship Society, finishes untying the ropes and hops in last, the ninth on board.

Generations ago, to get to the BC mainland, Haida people would have paddled across Hecate Strait from the archipelago of Haida Gwaii, their home turf 75 kilometers to the west. They might have exchanged dried halibut and red cedar canoes or boxes for items such as goat-hair blankets, horns, copper, and eulachon—a small, oily fish—with their trading partners. And, though at least one knowledge holder insists that the Haida’s reputation as fearsome warriors has been grossly overblown and that peaceful commerce was the norm, occasionally, they would also have come to settle grievances.

Skipper Bob Martin steers the Northern Lights along British Columbia’s north coast. Photo by Shanna Baker

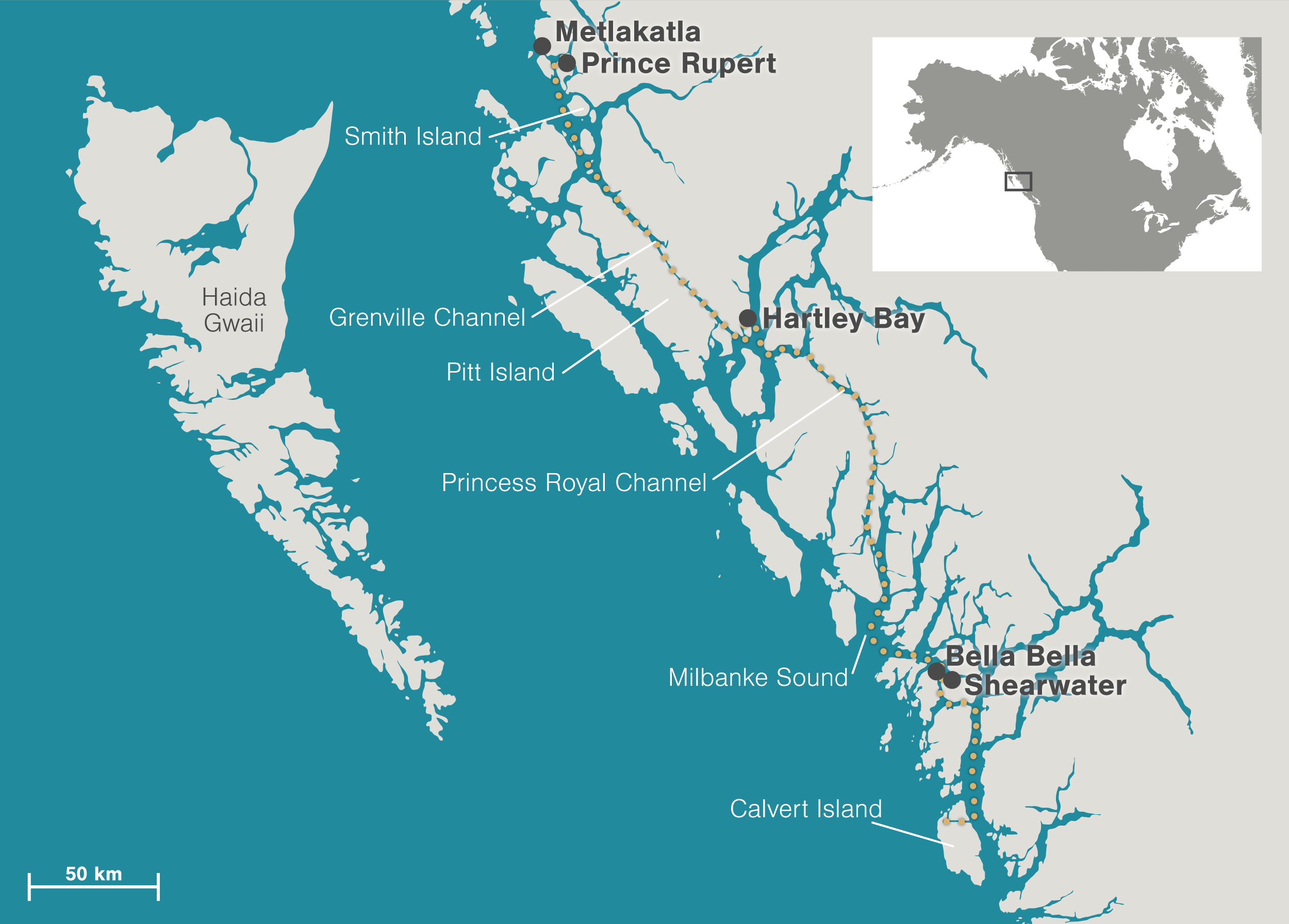

Today, the four men from the Haida Nation traveled over by floatplane instead, and to trade, they’ve brought a different kind of commodity: hard-won stories and insights gleaned from recent initiatives by their communities to manage natural resources. For the eighth year in a row, intellectual property will get swapped among some of British Columbia’s other coastal First Nations when they convene for the annual Coastal Stewardship Network (CSN) conference at Hakai Institute on Calvert Island, a full day’s journey to the south.

Martin navigates the aluminum-hulled Northern Lights away from Prince Rupert with Wilson on duty beside him to scan for prop-smashing logs. The water is stretched smooth here, and the feeble April sunshine creeps across the hulk of Smith Island as we motor past.

“I’ve been around this coast a few times,” says Clarence Nelson, a hereditary chief and elder from Metlakatla. The corners of his mouth curl, always on the brink of a grin, as he talks about his lifelong career as a fisherman. The conversation turns to a traditional feast he just attended. “I had grease,” he tells another passenger—shorthand for the coveted oil rendered from eulachon—“Oh, it was good.”

With the boat rocking and the horizon pitching, William Beynon of the Metlakatla Stewardship Society concentrates on the central coast scenery. Photo by Shanna Baker

Though the region is not immune to environmental pressures, to an outsider gazing at it through glass while buzzing by at 55 kilometers per hour, it is delectably wild, the kind of place that’s like a temporary hit of Prozac for quelling climate change anxiety. The narrow channel we turn down is bordered by dense forest that only stops when land abruptly collides with water. The people such as Nelson who have deep history here see a lot more nuance, of course: key locations for harvesting herring, former abalone hotspots, hidden cultural sites, and subtle markers on the landscape that signify home. Coastal First Nations know their respective territories better than most anyone else—which is why it seems obvious to all of the delegates on board that they should also take the lead role in managing them.

The CSN is a program of the larger Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative, and each of the eight member communities, based along BC’s north coast, central coast, and Haida Gwaii, employs a contingent of members to monitor fisheries, forests, and cultural sites. Collectively, these front-line workers, who carry out the day-to-day work of resource management for their nations, are known as coastal guardian watchmen (or sometimes watchmen, guardians, or stewards interchangeably).

“In our history, there were always three watchmen,” LaaDaa (Colin Richardson), the stewardship director from the Haida Nation explains. He leans forward, an eagle pendant shaped from silver dancing below his throat. “One looking out to sea and one looking down each side of the village.” Those three spiritual figures were carved onto Haida house frontal poles and were talismans against outside threats. “They were always carved like that,” he adds. “You never see watchmen looking back, they’re always looking front ways and sideways.”

As the coastal First Nations look for a future with more authority over their territory and resources, they also turn to the side—not to watch out for enemies now, but to find allies in their neighbors.

LaaDaa furrows his brow when I ask about the history of watchmen figures—did other coastal nations have similar iconography? “Are they coastal?” he calls to Sean Brennan, a former guardian watchman and now a delegate in consultations with the province, a few feet away. “The watchmen carved on poles, she wants to know if they’re coastal.” He shrugs. “I don’t know. All I know is we have them.”

“They’re Heiltsuk!” Wilson quips from his first mate’s chair.

“Oh! Okay! They’re Heiltsuk!” LaaDaa turns back to me, chuckling: “We still gotta be very gentle because we’re just starting to get along and we don’t want to piss each other off. So we have to walk on eggshells.”

The group laughs, over the background drone of the boat’s motors.

“I’m joking, but I’m also serious,” he says, dark eyes intent. “As we build our relationship back from a place where it wasn’t always so friendly, we’re building relationships. That’s really key. … We’re all working toward the same thing.” The Haida and Heiltsuk—like most of the coastal communities—have a long and complex history together, knotted with blood ties and close alliances, but also frayed with episodes of conflict, slavery, and war. In 2014, the two nations formalized an amicable working relationship with a peace treaty (first agreed to in the late 1800s), after protesting the Northern Gateway Pipelines project together.

At the far end of the cabin, Haida elder Captain Gold leans back, arms crossed, and stares out at the frosty dagger peaks of Pitt Island. Mirrored aviators and a black baseball cap from San Francisco boasting a fierce Chinese dragon shield his eyes. LaaDaa nods toward him: “They refer to him as the first watchman after the Ice Age.” Captain Gold half-smiles in response, but doesn’t change his gaze. He’s got the steady calm of someone perfectly suited to solitude.

It was 1973 when Captain Gold taught himself how to paddle a canoe and journeyed to the southern reaches of Haida Gwaii to SGang Gwaay Ilnagaay “to take care of the ancestors.” The village site had been abandoned during the 1880s after smallpox blazed through. During the trip, he sometimes found himself kilometers offshore, he explains after I slide into the seat beside him. He would battle with man-sized halibuts, while trying to avoid tipping. A fine white scar from one contest still spans the back of his left hand. When he reached the village, it was “a picture of neglect.” He made a fire and offered tobacco and food to the spirits. For years he worked alone, protecting the site from pillagers, welcoming the occasional group of kayakers, and keeping the rainforest from swallowing the carved poles and houses.

Mark Grinder, Captain Gold, and Sean Brennan from Haida Gwaii relax in Shearwater during a short break in the trip. Photo by Shanna Baker

In the early 1980s, his efforts led to the creation of the watchmen program on Haida Gwaii, with Haida ambassadors stationed at cultural sites across the archipelago. The concept—a more formal manifestation of what coastal peoples see as their responsibility to care for the natural world—spread from there. Indigenous groups from elsewhere in North America and countries abroad such as Australia have looked to the watchmen program for inspiration since.

At the gathering on Calvert Island, the 45 or so guardian watchmen and stewardship directors will discuss ways to funnel traditional knowledge from elders to younger guardian watchmen. Some will attend workshops on risk management and safety procedures, while the directors strategize how to establish authority through stewardship. They’ll analyze how events unfolded during a recent fuel spill in Heiltsuk waters near Bella Bella, to the south of us. And they’ll consider the possibilities of the newly announced CAN $25-million of federal funding for fostering Indigenous guardian initiatives over the next five years. Until then, with many hours of travel still to go, all there is to do is relax, bemoan the lack of cell service (“The Toronto Raptors are about to play”; LaaDaa and Brennan look downcast at their unresponsive tablets), and meditate on the scenery.

As we pass a particularly impressive jagged, white-capped peak, Captain Gold lifts his camera and snaps a photo, and then shows me how he can zoom way in to see tracts where large chunks of ice have broken free and tumbled down the glacier’s steep face. “We might see Sasquatches having a snowball fight,” he deadpans. “That’d make headlines.”

He points at a small pod of dolphins zipping across the water on our starboard side. They’re Pacific white-sided; Risso’s, another dolphin found in BC waters, moves a lot slower, he says. “Pacific white-sided dolphins are hyper, like they’re on sugar.”

After a quick stop at the community of Hartley Bay to pick up Gitga’at guardian watchman Don Reece and guardian coordinator Mary Reece, related through marriage, the chop becomes more aggressive and the jokes more intermittent. As we progress to Princess Royal Channel, the jagged waves transform into full-on breakers and the boat takes on a surge-and-smash cycle. Mary and I pass anti-nausea medication back and forth.

“You two look like a couple of apples,” Don says, looking first at Mary’s green hue and then at my flushed cheeks, from across the plastic-top table between us. “A Granny Smith and a gala.” At that point, green Mary bolts for the lavatory.

Nelson, the longtime fisherman, is unfazed. He puts his book down on the pitching tabletop to offer a suggestion for a not-so-traditional remedy: “My sister puts aspirin in her belly button,” he says with a grin.

Elder Clarence Nelson from Metlakatla takes in the view from Calvert Island before the Coastal Stewardship Network meeting gets underway. Photo by Shanna Baker

Every journey, as the trope goes, has bumps, figurative and literal (and in the case of this bumpy boat ride, that’s jarringly, spine-crunchingly literal). Since the stewardship network formed in 2005, the coastal nations have come up against grievances and occasional trust issues. But, at least to the people grinding down the central coast on the Northern Lights, the effort is worthwhile. “We’re starting to think more commonly as a coastal people, rather than individually as communities or nations,” LaaDaa says.

Before the network formed, a lot of the communities would only meet for basketball, at Northern British Columbia’s long-running All Native Basketball Tournament. “But that wasn’t always that good for building relationships, depending on who won or lost!” laughs LaaDaa. “With this, the opportunity is much greater.”

“We’re gathering with a common goal,” Brennan adds.

More than seven hours after leaving Prince Rupert, we finally sidle into Shearwater, where we swap boats, and motor over to Bella Bella to bring on eight more people, including a handful of members of the Heiltsuk Nation and some of the CSN staff, for the last leg of the journey.

As we turn into calmer waters, the malaise of the last couple of hours is forgotten, replaced with friendly chatter, as everyone turns to their neighbors.