Whales Through a New Lens

Forty years ago, the world’s whale researchers met in Indiana. The now legendary, but nearly forgotten, meeting changed the way scientists and the public see whales—and it all started with a few photographs.

Article body copy

Hunkered down on the torn leather back seat of a beat-up, borrowed Chrysler New Yorker, I read the conference program by flashlight. Eighty-four hours on the train and 900 kilometers by car had brought me from British Columbia to the unlikeliest place for a conference on whales: Bloomington, Indiana. After registration, I retired to my budget four-door bedroom, parked in the quietest, leafiest street I could find. It was November 1975; I was an aspiring author who’d just finished my third summer hanging out with killer whales off northern Vancouver Island. I was young and keen and eager to write a book about my experiences with the whales I was meeting: Stubbs, Nicola, Tsitika, and others. Crossing the continent for the National Whale Symposium at Indiana University Bloomington meant I’d be in the company of some of North America’s leading whale scientists. I could hardly wait for the talks to begin.

This was my first conference and also one of the first ever whale conferences. On the program were pioneering researchers—Roger and Katy Payne, Ken Norris, Mike Bigg, and a few dozen others, all who had ventured far from their respective homes to a midwestern state far from the ocean. In those days, fax machines were rare, and there was no Internet. Journal articles took longer to publish and reach university libraries, much less be read. It would still be years before there was a professional society or journal devoted to whale research, so a conference was the only practical way to exchange ideas.

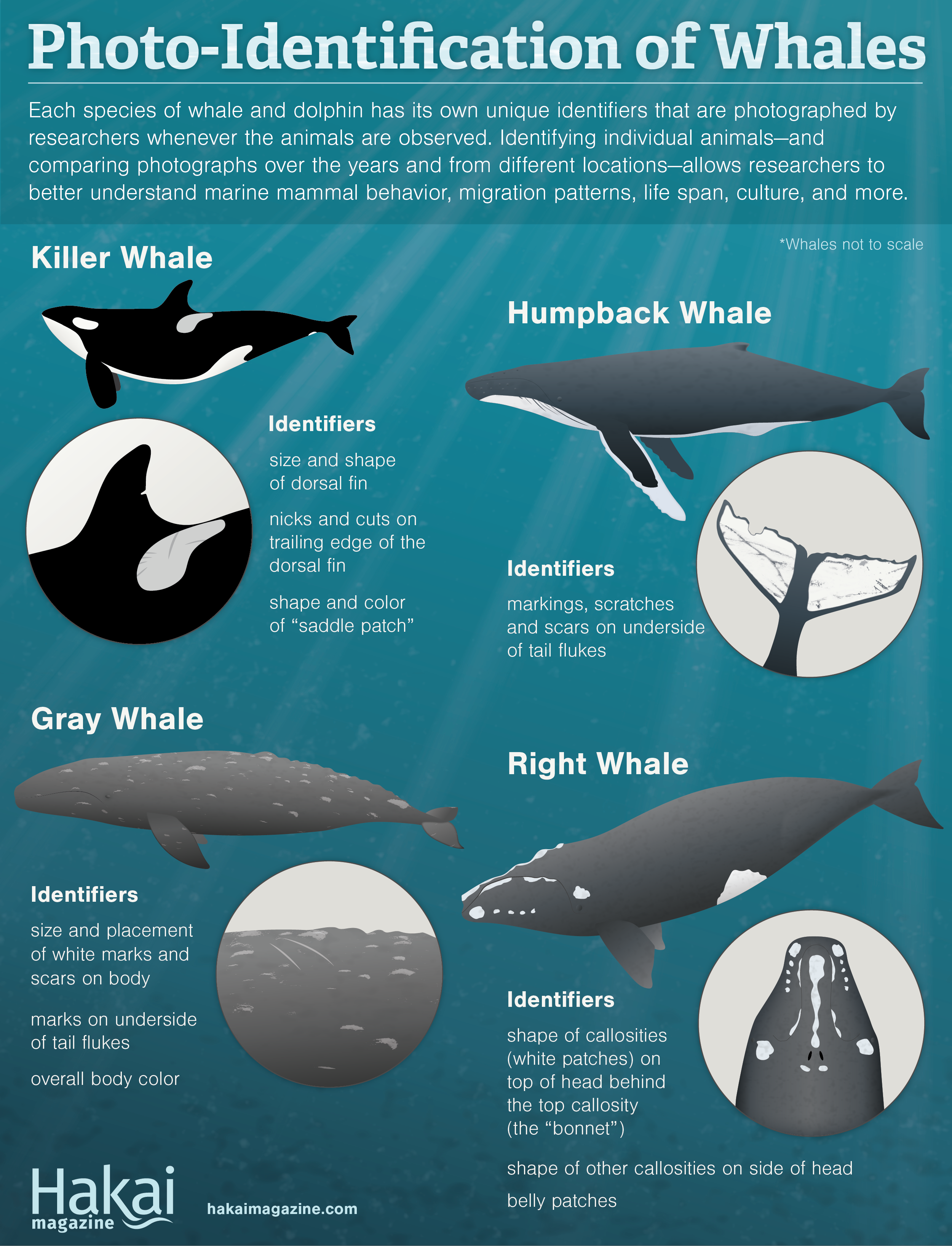

The conference buzz was photo-identification, or “photo-ID.” Around the world, researchers were simultaneously developing a new method of studying individual whales by photographing distinctive body parts. But given the patchy connection of the world back then, they were largely unaware of each other’s work. This conference would change that—and unlock the door to studying the hidden lives of whales.

The idea of whale photo-ID seems simple. You take a sharp photograph of a whale’s distinctive fin, tail flukes, head, and/or back, depending on the species; log the time and location; and then—when you re-photograph that whale days, months, or even years later—you have pieces of a scientific puzzle you can combine to tell a story. In practice, taking photographs suitable for photo-ID is an acquired skill that depends on good light, reasonable seas, and timing—predicting the precise spot in the ocean where the whale will appear and managing to focus and fire the instant the whale surfaces. Try doing that wearing gloves and a bulky survival suit or life jacket while crammed into a small boat in choppy seas.

The unique markings on the underside of a humpback whale’s tail are used to identify individuals. Photos of the tails are compiled into catalogs which are used by researchers investigating the life history of these animals. Photos by (clockwise from top left) Ingo Arndt/Minden Pictures/Corbis, Tom Soucek/AlaskaStock/Corbis, Ashley Cooper/Corbis, Joe McDonald/Corbis

The conference program didn’t specifically mention photo-ID, and there was almost nothing published about it at the time, although a 1974 paper by British Columbia researchers Jim Darling and Dave Hatler had noted a distinctively marked gray whale they’d repeatedly seen off the west coast of Vancouver Island. But, as we’d soon learn through conference conversations and from papers published in the years to follow, scientists around the world were noticing that the whales they studied had individual, unique markings. This synergy was a momentous turning point in the study of whales.

The conference star was Roger Payne. In the late 1960s, Payne and Scott McVay had discovered humpback whale songs and, in 1971, published their findings in Science. Around the same time, Payne’s record album “Songs of the Humpback Whale” made the Billboard 200 chart and stayed there for eight weeks. It became the best-selling natural history record of all time. In the midst of his work on humpback songs, in 1970, Payne moved with his wife Katy and young children to “Whale Camp,” on the cliffs of Patagonia, in southern Argentina, to live among southern right whales, which were beginning their long recovery from intensive whaling.

At the conference, Payne talked about his right whales, played whale recordings, and showed films of his family adventures. He described how, after hours of observation, he realized that he could use the white markings on the head of a right whale to tell individuals apart. Payne and his team began taking aerial photographs from a small plane, capturing on film what turned out to be distinctive patterns of callosities—the characteristic rough, white patches of skin, unique to right whales.

By 1973, Payne and his team had started using photographs to match whales seen in previous years. One of the first southern right whales to be photo-IDed, however, was matched using a white belly patch not a callosity. In 1970, Payne had photographed a whale swimming belly-up, accompanied by a calf. The adult whale would come to be known as Troff. The calf disappeared but a few years later, researcher Eleanor “Ellie” Dorsey, then working with Payne in Patagonia, matched a photo of a whale’s belly markings to that first 1970 photo—Troff was back at Whale Camp and she had a new calf in tow. Payne and his colleagues were beginning to see the rich potential of photo-ID.

Southern right whales in Patagonia were some of the first whales to be photo-identified. Photo by Paul Souders/Corbis

Also at the Indiana conference, Steven Katona, from College of the Atlantic, in Bar Harbor, Maine, talked about the humpback whale tails he’d been photographing in the Gulf of Maine since about 1970. (Humpbacks are the easiest of all whales to identify individually because they surface three or four times, allowing the boat and photographer to get into position. When they dive, the whales flip their tail flukes high out of the water, revealing the telltale white-and-black pigmentation patterns on the underside.) A year after the conference, Scott Kraus, then a College of the Atlantic student working with Katona, compiled the first basic humpback tail fluke catalog. That became the North Atlantic Humpback Whale Catalog, which is still curated by College of the Atlantic and today includes photos of more than 8,000 different humpback whales.

The idea of photo-identifying whales began to coalesce around the Indiana University conference, yet individual identification of animals by scientists was not new. In the 1930s, ethologist Konrad Lorenz recognized individual greylag geese through natural markings and behavior in his studies of imprinting. And when students of Lorenz, and his colleague Nikolaas Tinbergen who founded Oxford University’s animal behavior department, took to the savannas of Africa, individual identification was adopted for studies of zebras, giraffes, elephants, and lions. The insights of Jane Goodall into chimpanzee behavior depended in part on her ability to recognize individual animals from their natural markings.

Why did it take so long for photo-ID to be tried with whales? Partly it was the difficulty of working with fast-moving animals that spent most of their time underwater, and appeared at the surface only briefly. Also, the centuries of heavy whaling in every ocean—which only began to wind down in the late 1960s—had removed nearshore populations.

As the whales started returning to the coasts in the early 1970s, researchers equipped with relatively inexpensive, hand-held single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras, came out to meet them. Many of these researchers were 1960s idealists living in a time of cultural upheaval when questions were being asked that had few answers, when authority and the ways of doing things were being challenged, and when a flagrant disregard for the environment symbolized by the near-obliteration of whales became a rallying point. Many began to consider the intelligence of whales and dolphins and they looked to the study of wild whales for answers.

Photo-ID became the single-minded obsession of many researchers. Little did we realize the promise that it held to provide whales with a backstory, a personal narrative that could give context to their lives. Still, photographing one whale at a time was never going to be a quick way to learn about marine species that spend most of their time underwater and cover vast distances. The success of the tool would rely on the accretion of data over many years and cooperation among researchers as far flung as the whales.

Early evidence of the power of whale photo-ID came in 1979 when Jim Darling, who studied Hawaiian humpback whales as well as Pacific grays, took a stack of photos to Alaska. Darling wanted to compare his Hawaiian humpback images to those taken by researcher Charles Jurasz on the whales’ Southeast Alaskan feeding grounds. At that time, scientists assumed humpbacks from Hawaii were migrating to the Aleutian Islands, 2,400 kilometers west of Southeast Alaska, to feed.

Darling played host to the landmark slide show in his hotel room in Juneau. The first slide Jurasz projected on the wall looked familiar to Darling. He rifled through his prints and pulled out one that appeared to match. “Well it was so close,” he says, “we couldn’t believe it. But the photo was a little fuzzy, so we didn’t count that one.” The third slide, however, was a definite match: it was the first time photographs were used to help understand the migration routes of humpbacks in the Pacific.

Whale researcher Jim Darling prepares to photograph the identifying features of humpback whales in Southeast Alaska. Photo by Flip Nicklin

Darling was astonished to find many more matches between Hawaii and Southeast Alaska. Weeks later, he compared photographs with Katy Payne who had spent the winter recording songs in Mexico. He found some of his Hawaiian humpbacks in her photo-ID collection. These assorted slides and black-and-white photographs showed that humpbacks were not only traveling great distances, but that certain humpbacks were changing their breeding grounds from year to year, switching between Mexico and Hawaii.

The collaborations continued and through subsequent matches of photo-ID shots, researchers around the world identified many other whale migration paths and unpredictable movements. For instance, Troff, the southern right whale first photo-IDed by Payne, revealed a surprising change of habitat. Researchers encountered the young mother in Golfo San José, Patagonia, Argentina, over seven seasons between 1970 and 1981, with three separate calves. But then, in 1988, she swam to southern Brazil, 3,000 kilometers farther north and raised a calf there. She returned to Brazil in 1994, but by 2004 was back in Golfo San José.

“We’re following the lives of known southern right whale individuals in the South Atlantic extending even to Antarctic waters,” says Mariano Sironi, scientific director of the Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas in Argentina. This information helps determine the whales’ biological and conservation needs. Sironi and other Argentine biologists, along with southern right whale researcher Vicky Rowntree and the group Ocean Alliance, based in Massachusetts, are continuing Roger and Katy Payne’s work in Patagonia. Through photo-ID, we know that females have their first calf at age nine and have one calf every three years on average, Sironi says. “And thanks to Troff and other whales, we now know that conservation strategies to protect right whales in the South Atlantic can only be effective if we include large oceanic areas that extend from southern Brazil to the Antarctic.”

As the revelations from photo-ID spread to every ocean, scientists were surprised to find unexpected migration events, such as the South Pacific humpback whales that cross the equator to breed. The drive to get inside whale societies—not just to identify the individuals, but to understand how families and other groupings worked—became the holy grail for those engaged in long-term studies of toothed whales and dolphins, and particularly of killer whales.

For me, the highlight of the Indiana University conference was listening to Mike Bigg from the Pacific Biological Station, operated by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, which was located in Nanaimo, British Columbia, not far from where I spent my summers watching killer whales. I had met Bigg often in the field, and, he, along with colleagues Ian MacAskie, Graeme Ellis and, later, John Ford and Ken Balcomb, were studying killer whales on the BC and Washington State coasts, trying to get a peg on population size, particularly since the pressure to capture killer whales for aquariums remained strong into the early 1980s. Photographing whales was the bread and butter of their work and through it they were beginning to see associations between individuals.

At Bloomington, I shared with Bigg the photos I’d taken the past summer with expedition mates Peter Vatcher and John Oliphant. Bigg recognized the whales and rattled off their names—Scimitar, Nicola, and Sharky—noting a few new nicks here and there. Impressed by our work, Bigg asked me to take photo-IDs on a contract basis at $15 per useable photo. It would be enough to finance another summer expedition.

The charismatic killer whales I’d been privileged to spend three summers with were becoming the best known and recognized of any of the photo-IDed whale populations anywhere. Our understanding of their biology and social life stems from those pioneering photo-ID years.

Mike Bigg and his colleagues’ photo-ID work would eventually unlock the complex and highly structured social system of killer whales. In 1983, when I interviewed Bigg for National Geographic, he spoke about killer whale matrilines, the close associations of the animals to their mothers. He was struggling to understand the life cycle of the pod, how new pods got started. The answer, he said, “probably lies in the thousands of dorsal fin photographs showing the associations over many years between all these individuals of each matriline in each pod.” And he was correct.

Through years of repeated observations and photographs, Bigg and others learned that salmon-eating killer whale societies are based around females and their calves, with the males staying with their mothers for life. And when female calves in a pod mature and start having their own calves, they start to form matrilines after their own mother dies. On average, females have five calves spaced over 25 years from about age 15 to 40, and then live a further 10 or more years as “grannies.” The old female Stubbs, my personal favorite and the one I had spent hours with in the summers of 1973 and 1974, was the first killer whale ever identified in Bigg’s alpha-numeric system, where a letter identified the pod and a number cued to the particular individual. Stubbs was known as A1 in the BC-Washington killer whale catalog. This catalog comprised a collection of photographs of individuals sorted into pods that went from A to Z to include about 20 pods and more than 50 matrilines off northern and southern Vancouver Island. When Stubbs died in late 1974, she was estimated to be at least 47 years old, having served some seven years as a grandmother; Bigg predicted (accurately) that some females would live beyond age 80. “These whales are so long lived,” said Bigg. “New pod formation must be happening very slowly—on a scale of hundreds of years.”

Mike Bigg, who died of leukemia at the age of 50 in 1990, was a pioneer who made a lasting mark with his work. He was also inclusive, encouraging the public as well as other researchers to contribute and collaborate. The body of work from Bigg and colleagues has provided extremely accurate population counts as well as detailed family trees of killer whales. John Ford, who currently occupies Bigg’s position at the Pacific Biological Station, helped to shape this understanding of killer whale societies through his studies of killer whale dialects, work that built on the detailed photo-ID records of each pod.

That photo-ID helped researchers to understand how whales communicate underscores the lasting value of this technique. The photogenic killer whales demonstrate photo-identification’s incredible potential, where decades of photo-ID work is the building block for understanding killer whale genetics, feeding behavior, and the differences between ecotypes, from the fish-eaters to the marine-mammal hunters to the various whale-, penguin-, and seal-eaters of the Antarctic. Killer whale research around the world, from Norway to the Strait of Gibraltar, draws and builds on these studies.

Individual killer whales can be identified by unique characteristics such as the size and shape of the dorsal fin and the shape of the white “saddle patch.” Photos by (clockwise from top left) Flip Nicklin/Minden Pictures/Corbis, Galen Rowell/Corbis, Amos Nachoum/Corbis, Ian McAllister/All Canada Photos/Corbis

Today, 40 years after the Indiana University conference, photo-ID catalogs exist for hundreds of populations of whales and dolphins around the world. One of the largest catalogs, covering humpback whales in the North Pacific, includes more than 18,000 photo-ID records of nearly 8,000 individuals. For fast-moving oceanic dolphin species with tens or even hundreds of thousands of individuals, photo-ID of every individual is problematic. Because dolphins are so social, however, researchers can photograph well-marked individuals from specific groups to establish movements, habitat use, and site fidelity.

Photo-ID techniques continue to evolve; the flexibility and low cost of digital photography helps. Recently, researchers have started using drones to take aerial ID photos. Yet a sharp photo taken on a smartphone can be just as scientifically valuable. For example, low-resolution photos posted on Facebook were recently used to help create the first photo-ID catalog for rare North Pacific right whales off Russia and Japan.

Whale researcher Hal Whitehead describes how photo-ID is an integral part to understanding whale societies.

At the Indiana University conference, the program featured whale films, music, photography, art, and literature—human culture about whales. Today, a hot area of research investigates whale culture—defined with care and formality in Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell’s 2015 book, The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins, as “information or behavior—shared within a community—which is acquired from conspecifics through some form of social learning.” The roots of this began with photo-ID in the 1970s and with the ability to identify individual animals. We could see evidence of a “cultural life” at the “rubbing beaches” on Vancouver Island where killer whales gathered in the shallows to rub their skin on the pebbles and sand, and in our growing understanding of humpback whale songs that the males change throughout the breeding season, and of killer whale dialects passed from mother to offspring. Culture was also evident in the specific learned hunting techniques used by killer whales and other whales and dolphins. Around Península Valdés, Argentina, for instance, researchers watched killer whales teach their calves how to strand on beaches in order to hunt sea lion pups. Parents not only modeled stranding techniques, but also how to wriggle back into the water. And in 1997, scientists in Australia noticed that certain bottlenose dolphin mothers taught their young how to carry a sea sponge at the tip of their beaks to help protect them from rocks, urchins, stingrays, and other surprises while foraging for food. These were all local behavior patterns, a cultural transfer of information passed between individuals; the behaviors were not hard-wired, genetic inheritances.

The study of whale culture “came out of our appreciation of whales and dolphins as individual animals,” says biologist Philippa Brakes from Whale and Dolphin Conservation who co-edited with Mark Simmonds Whales and Dolphins: Cognition, Culture, Conservation and Human Perceptions (2011). “From there, along with the primates, we have moved toward a consideration of rights for these individual animals.” This sense of “personhood” led Brakes and others to convene a workshop in Helsinki in 2010 where a charter of cetacean (whale, dolphin, and porpoise) rights was drafted. Whitehead, who had worked in the early years with Roger Payne, was there, too. In sum, the declaration stated: “We affirm that all cetaceans as persons have the right to life, liberty and wellbeing.”

If photo-ID has led to an understanding of cultural behavior in whales and to the quest for whale rights, part of that may also be due to certain shifts in human culture that began 40 years ago. A new generation of scientists started paddling out to see whales, to take photos and share information, and to develop ocean-wide photo-ID catalogs of various whale species that have become the cornerstone for much of what we’re learning about whales. Like the transmission of whale culture, there has been a transmission of whale researchers’ culture as these scientists pieced together the stories of whale societies literally one photograph at a time.