Canada’s New Marine (Less) Protected (Than It Could Have Been) Area

A string of concessions to the oil and gas and fishing industries has severely weakened the protective value of Canada’s largest planned marine protected area.

Article body copy

Canada is about to get its largest marine protected area: 11,619 square kilometers in the Laurentian Channel off the southwest coast of Newfoundland. This summer, the Canadian government will begin the process to establish the area, which has been in discussion for seven years. It sounds like a huge win for the environment, but the area’s final boundaries and regulations bear the heavy hands of industry, according to Rodolphe Devillers, a geographer at Newfoundland and Labrador’s Memorial University who helped identify the area as a conservation priority. Now he’s asking whether this protected area and others to follow will actually safeguard at-risk species. And if not, why bother creating them?

It’s an important question, especially now, because Canada has adopted a set of goals to protect the environment in accordance with the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi targets. Among Canada’s goals is to designate 10 percent of its territorial waters—about 575,000 square kilometers—as marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2020. Only one percent is currently protected, and with an interim target of five percent by the end of this year, the government is crunched for time.

Sigrid Kuehnemund, a marine biologist and lead specialist for oceans with World Wildlife Fund Canada, is worried that in order to hit its targets, the government may cut corners. “It’s important to ensure that the quality of MPAs isn’t being sacrificed in the race to meet targets,” she says.

Yesterday, Devillers presented his findings at the meeting of the Canadian Society for Ecology and Evolution in Victoria, British Columbia. His presentation documented how the Laurentian Channel MPA was sliced and shrunk during the planning process as Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), the federal department in charge of fisheries and waterways, accommodated stakeholders.

Concessions made to the fishing and oil and gas industries make the reserve significantly less useful for conservation, Devillers says.

First, the Laurentian Channel was chosen over 10 other sites proposed by scientists because it was the site with the fewest objections by industry, says Devillers. After negotiations, fishing will not be allowed within the MPA, but prime fishing areas originally included in the proposed area were sliced off, and cod and redfish were removed from the list of species of concern.

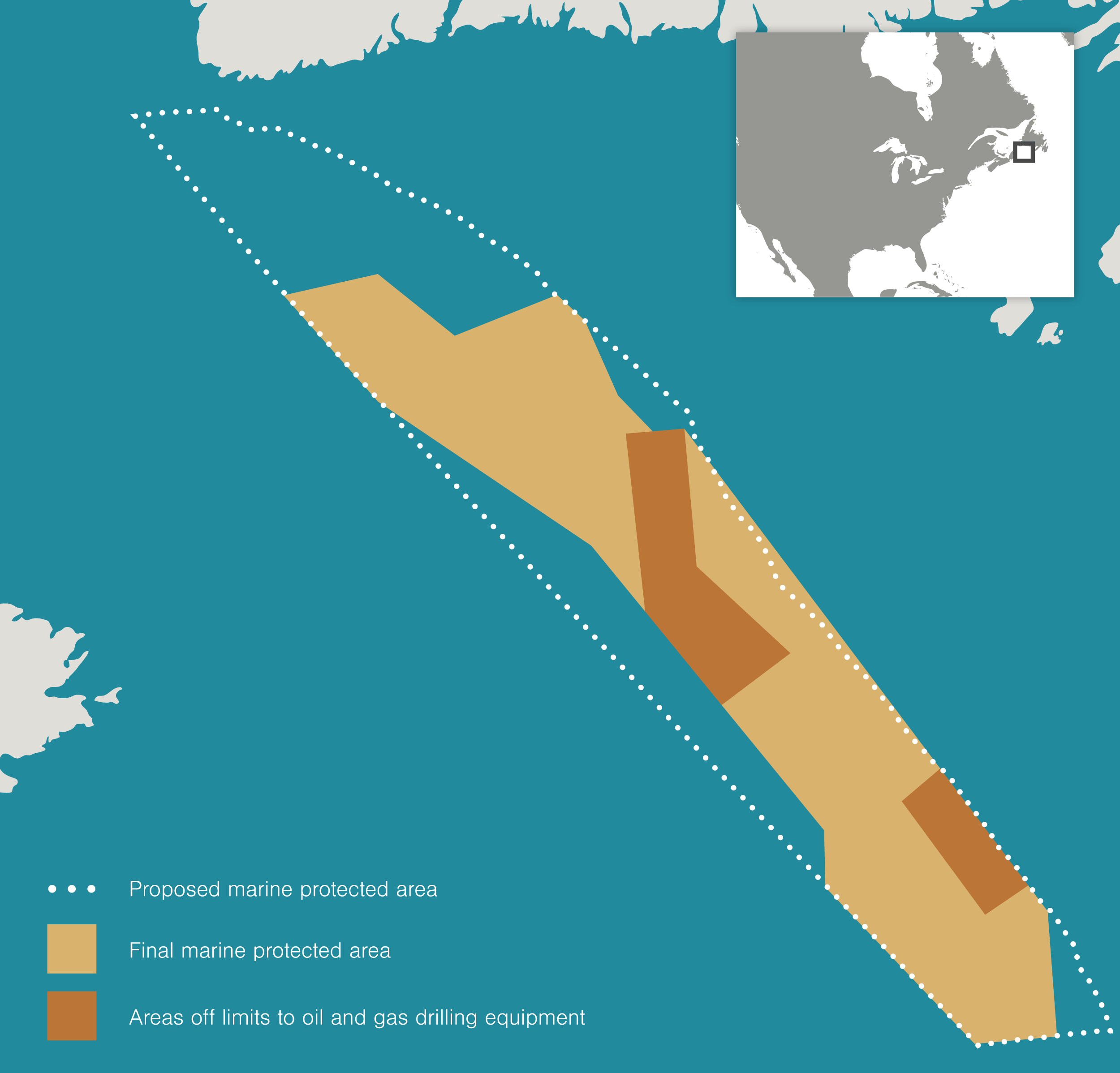

Oil and gas drilling will also be allowed in 88 percent of the MPA. The habitat of delicate sea pens (a type of soft coral) will be off limits to drilling equipment, but directional drilling from just outside that inner boundary will still allow the oil and gas industry to extract fossil fuels from 98 percent of the MPA. The off-limits area was also further reduced from its original size after lobbying by industry. Shipping will also be allowed throughout the MPA.

“If you have an oil rig in Banff National Park, people are going to see it, and they are going to say, ‘Bah! This makes no sense!’” says Devillers. But he thinks people have different standards for marine parks than terrestrial parks, likely because they have little awareness of what goes on in the ocean.

The originally proposed boundary for the marine protected area (in dotted white), and the final boundary (in orange). Illustration by Mark Garrison

Kuehnemund says the seemingly counterintuitive move to allow oil and gas drilling in a protected area, which WWF-Canada opposes, is a function of the three different ways Canada can create marine protected areas.

The Laurentian Channel MPA is being developed under Canada’s Oceans Act, which is regulated by DFO. This pathway is often the most industry-friendly way in which a protected area can be created. One of DFO’s stated goals for MPAs is “to contribute to the social and economic sustainability of coastal communities.”

The two other avenues for creating MPAs could have resulted in stronger protections. Marine National Wildlife Areas, created by Environment and Climate Change Canada, have protection under the Canada Wildlife Act. And the National Marine Conservation Areas Act allows Parks Canada to establish marine parks.

Steve Snow, DFO’s regional manager for the ocean program in Newfoundland and Labrador, defends the compromises that led to the Laurentian Channel’s reduced boundaries. “You can include human activities as long as they don’t contravene the conservation goals,” he says.

For the Laurentian Channel, the stated conservation goals include specific objectives for six key species, including sea pens, black dogfish, smooth skates, porbeagle sharks, northern wolffish, and leatherback sea turtles. The original list had 16 species.

The Laurentian Channel MPA is intended to protect a range of at-risk species, including the northern wolffish. Photo by imageBROKER/Alamy Stock Photo

Yet after corners of the proposed MPA were sliced off to accommodate fishing, reducing the protected area by 33.4 percent, Devillers’ calculations project a decline of up to 43 percent in the abundances of these six key species.

Fish, Food and Allied Workers is a fishing industry organization representing owners and operators of fishing boats fewer than 25 meters long. The organization’s secretary treasurer, David Decker, says “communities are built upon the resources of the sea,” and therefore his organization supports a healthy ecosystem. A different fishing organization representing corporate fleets, Groundfish Enterprise Allocation Council, advocated for cutting out key cod and redfish fishing areas, he says.

Still, Decker says, the whole notion of an MPA to protect fisheries “is naive, quite frankly,” because fish move in and out of a protected area.

But quotas based on good science and input controls, such as the amount of gear permitted and the length of the fishing season, help ensure sustainable fisheries, Decker says.

Not surprisingly, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) was pleased with the outcome of the stakeholder negotiations. Paul Barnes, CAPP director of Atlantic Canada and the Arctic says, “We felt the Laurentian Channel was a very good, balanced MPA, in line with the principles of the Oceans Act … balancing conservation with economic development.”

To those who question whether conservation got any concessions in this deal, Barnes and Snow point to the sea pen exclusion area and to the seasonal restrictions on seismic testing meant to protect porbeagle sharks during their pupping season and leatherback turtles during their migration.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the fishing industry is used to working alongside oil and gas, says Decker. But to go into a traditional fishing area and exclude fishing but allow oil and gas, “What message does it send? I think it says those who are most powerful get the win.”

But oil and gas drilling isn’t allowed in all MPAs, says Kuehnemund, adding that WWF-Canada is “very encouraged” that other planned MPAs, such as the proposed St. Anns Bank protected area, east of Nova Scotia, will exclude oil and gas activities.

For Devillers, the most worrisome point is that after the concessions to industry, independent scientists were not called upon to evaluate whether the Laurentian Channel protected area’s new boundaries would still work for the intended conservation goals.

“It would be like having an architect designing a house, and then you get 50 people discussing how to change the house, but the architect is not involved,” he says. “At the end, the house may not stand anymore because everybody has changed everything, from the foundation to the roof to the walls.”

DFO’s Snow disputes that characterization—sort of. “The process is science based and evidence based,” he says, “but at the end of the day, [the protected area’s] social and economic goals are also really important.”

Devillers says the Canadian government is not transparent about whether it is meeting its conservation goals. He cracked, “We don’t muzzle scientists anymore in Canada, but that doesn’t mean that we listen to them.”

In April 2019, Fisheries and Oceans Canada outlined new rules governing industrial activity in marine protected areas, and the situations in which marine refuges will be counted toward Canada’s conservation quotas. Read more about that in “Canada Has New Rules Governing its Marine Protected Areas. Do They Go Far Enough?”