A New Treatment Could Save Sea Lions from a Deadly Algae

Researchers are testing to see if alpha lipoic acid can halt the toxic effects of domoic acid.

Article body copy

A sea lion pokes his head out of the water and swivels it around like a periscope. Apparently liking what he sees, he flings himself over the pool’s concrete lip and onto dry land. He grunts and scans the perimeter again, hoping for fish and looking much healthier than when he arrived. Many sea lions like him ended up here, at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California, after they were poisoned by toxic ocean algae.

The center, a research and animal rescue center built atop a decommissioned Cold War missile launch site, overlooks the Pacific Ocean, and from his new perch this sea lion can see the sea—the home that he was pulled from in a bid to save his life. This male is one of 217 sea lions that were brought to the center this year after they were poisoned by a huge bloom of toxic algae.

Visitors watch sea lions in their pools at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California. Photo by David Wakely/The Marine Mammal Center

Over the past few years, unusually warm ocean water has been disrupting marine life up and down North America’s west coast. This temperature hike has proven to be a perfect breeding ground for the harmful algae Pseudo-nitzschia australis. At its maximum extent, a bloom of it stretched from California to Alaska. It’s been the most harmful P. australis proliferation in 15 years.

P. australis corrupts the food web. When small fish eat the algae, they ingest a toxin called domoic acid, which has no ill effects on them. Sea lions then eat the fish, and the accompanying domoic acid. Because the sea lions are eating many fish, the toxin gets concentrated in their bodies.

Domoic acid is nasty stuff for vertebrates like sea lions. It targets the brain (specifically, the hippocampus) leaving sea lions lethargic and disoriented. And as the poisoning becomes more severe, so do the symptoms. “We’ll see them on our beaches seizing,” says Claire Simeone, a veterinarian at the center. “They may be comatose.”

People who ingest too much domoic acid don’t fare well either, getting a condition called amnesiac shellfish poisoning.

Without proper veterinary care, sea lions afflicted by domoic acid poisoning will experience progressively worse seizures, paralysis, coma, and, eventually, death.

Those lucky enough to be found passed out on beaches from Mendocino County in Northern California to San Luis Obispo, nearly 650 kilometers south, wake up in a new home on the Golden Gate Strait, just across from San Francisco.

Coast guard, lifeguard, and rehabilitation center staff work together to carry a pregnant sea lion that was poisoned by domoic acid further south in California, in Santa Monica, in 2011. Domoic acid poisoning is a recurring problem that seems to be becoming more common. Photo by Jonathan Alcorn/ZUMA Press/Corbis

When an animal with advanced symptoms arrives at the center, the first step is to control its seizures. The vets give it phenobarbital, the same drug doctors give people who have seizures. Once the sea lion is stable, vets begin treatment with fluids to flush the toxin out.

In most cases, “we are able to support them through that time. In a couple of weeks, they are back to normal behavior,” says Simeone. But even still, this treatment is no cure.

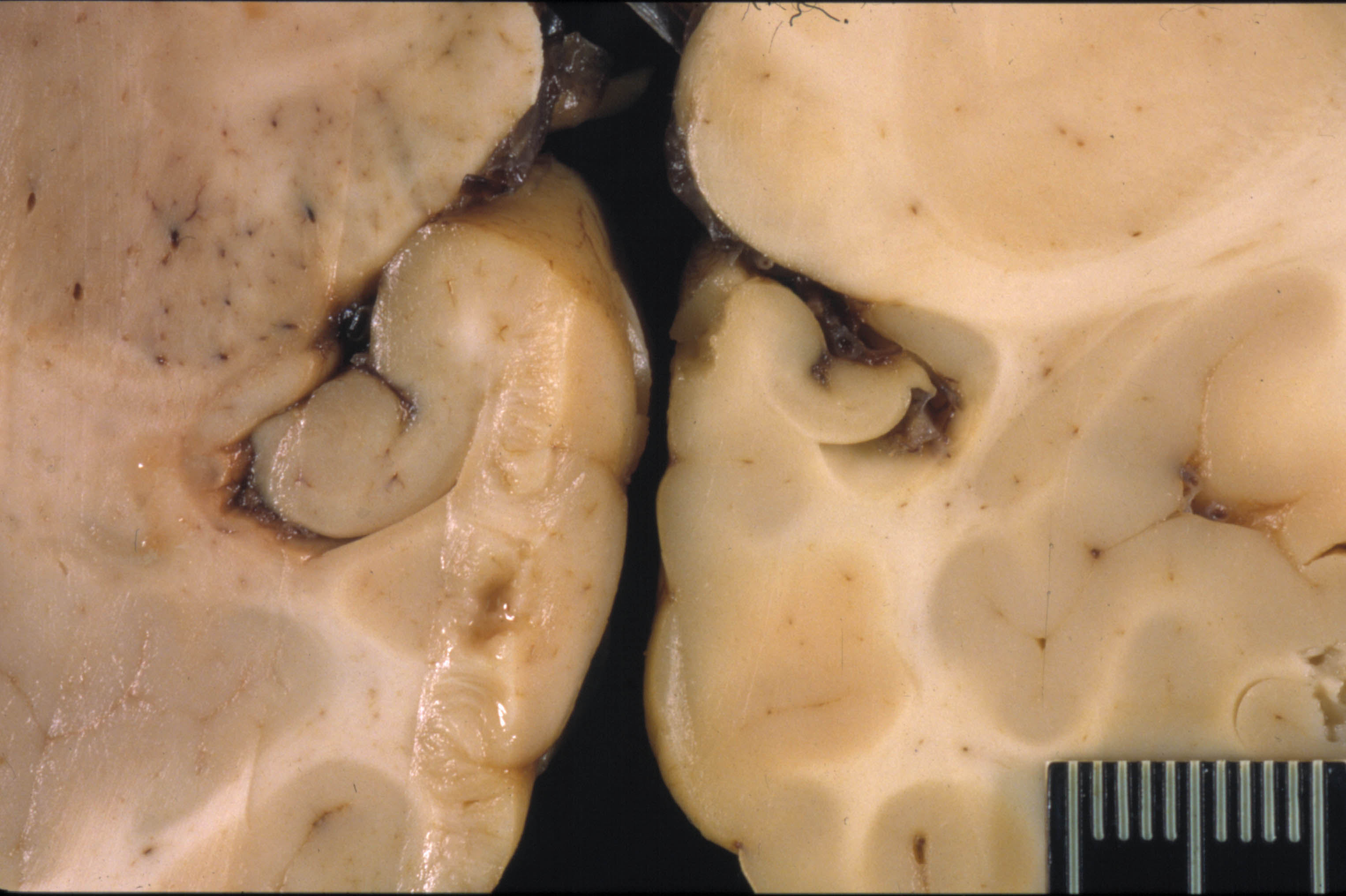

Though a sea lion’s body will eventually clear the toxin, the animal is “left with inflammation in the brain,” says Simeone. That inflammation can cause cells in the brain to die long after the toxin is cleared, and the sea lions’ brain lesions are almost identical to those seen in humans who have temporal lobe epilepsy. Sea lions who keep eating poisoned fish experience cumulative effects. Treating the sea lions’ symptoms can help save their lives, but it’s not a long-term fix.

That’s why, this year, the vets are testing a new addition to the standard mix of phenobarbital, rest, and fluids: alpha lipoic acid, an antioxidant that is used in humans to treat conditions such as dementia, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. Alpha lipoic acid combats damage in the brain and heart, by decreasing inflammation and helping tissues regenerate.

A sea lion’s brain affected by domoic acid (right) shows a shrunken hippocampus, in the center of the photo, as compared to a healthy sea lion brain (left). Photo by The Marine Mammal Center

So far, nearly 60 percent of patients who went through this year’s treatment were able to be released back into the wild, with the extra protection of the antioxidant treatment, which will hopefully keep their brains healthier for longer. “Based on studies in other species, we think this treatment will provide some protection from the damage caused by domoic acid,” says Shawn Johnson, the center’s Director of Veterinary Science.

If this new approach works, it won’t be a minute too soon.

P. australis blooms used to be seasonal, says Simeone. But now, because of increasing oceanic temperatures, toxicity cases are appearing throughout the year. And species other than sea lions have been showing up with seizures, signaling the toxin’s progression through the ecosystem. The coming year could prove particularly difficult.

“We’re bracing ourselves because of the projected El Niño,” says Simeone. “We expect to be very busy, because that includes warmer water temperatures. We don’t know whether or not this is the new normal.”

And if it is the new normal, research into new treatments like this one will become even more essential in the battle to save sea lions.